Chinese Calligraphy in Tsao Shu (Running Style) 草 書

Updated: 02/15/2013

Tsao

Shu (also known as Grass Style, Running Script, Caoshu, Cao Shu, or Cursive Script) is the most

simplified but abstract and difficult form of writing in Chinese calligraphy.

Among all Chinese calligraphy styles, Tsao Shu usually demands the highest

levels of techniques while expressing the maximum freedom (in conformity with

many complex rules.) Tsao Shu was developed almost at the same time with Li Shu. Since the Han

Dynasty, Li Shu and Tsao Shu were developed and established. From the

Han Dynasty to the Jin

and Tang Dynasties, there were many

famous Tsao Style calligraphers. Tsao Shu reached one of its peaks during the

Jin Dynasty when Wang Hsi-Chih and his son, Wang Hsian-Chih, were both good at this style.

The father and son are referred as "the Two Wangs"

( 二

王

) in the Chinese calligraphy history. They influenced

later calligraphers in each dynasty, especially for Hsin and Tsao Styles. Later

in the Tang Dynasty, two great calligraphers, Zhang

Hsui ( 張

旭

)

and Huai Su ( 懷

素

),

were both reaching another peak in Tsao Shu.

Tsao

Style is generally considered the most difficult style among all five major

Chinese calligraphy styles. Calligraphers specializing in Tsao Style decreased

in number since the Tang Dynasty.

The

main feature of Tsao Shu is to simplify the left sidepiece (radical) of a

character and focus on the right sidepiece (“Yi Zuo Yang Yu 抑

左

揚

右,” literally simplify the left and

focus on the right.) Thus a calligraphy work in Tsao Style will look more

smooth, connecting and faster with abrupt turning and dramatic effects.

The following is a chart that lists each character in Kai Style and three ways of writing that character in Tsao Style. Like Zuan Style, a character can be written in many ways in Tsao Style.

From

the above examples, we may know that “simplifying the left and focusing on the

right” is

a major rule for creating a Tsao Style character by different ancient

calligraphers. The calligraphers obey the prototype more strictly on the left

side while they have leeway for artistic design on the right side. If a laymen

tries to coin his way of creating a Tsao Style character without learning and

basis,

he may end up making mistakes. Adding or removing a single dot in one position

can turn a Tsao character into another one. For example, “Wei #2” and “Zu

#3” are just different in one dot. There

are innumerous close differences or similarities like this since the total number of Chinese

characters is so large.

If

art does not impose some norms or standards, everybody can do it in his

own way without learning and practicing. Consequently, people won’t appreciate

or recognize each other’s efforts and contribution. Just as languages and music have their own

grammars, Chinese calligraphy has sets of strict rules, especially for Tsao and

Zuan Styles.

During the Emperor Zhang’s ( 漢 章 帝 ) reign in the Han Dynasty, calligrapher Du Du ( 杜 度 ) was allowed to present documents in Tsao Style to the emperor. Thus his Tsao Style was called “Zhang Tsao 章 草.”

Emperor

Zhang’s calligraphy

After Du Du, there were Tsui Yuan, Tsui Shu, Zhang Chih, and Zhang Tsun. Among them, Zhang Chih ( 張 芝 ) was the first calligrapher to earn the title “King of Tsao Shu 草 聖 ” and he taught many students. He was the founder of the modern school of Tsao Shu (“Jin Tsao 今 草 ”, "Jin" means today or modern.) He had a great influence on Wang Hsi-Chih and especially Wang Hsiang-Chih. During this era, there were many schools of Tsao Shu and Tsao Shu became very, very popular in all walks of life and had a great impact on the whole nation and society.

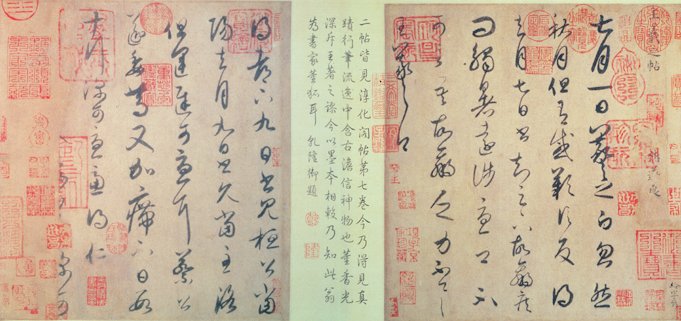

Tsao

Style works

by Zhang Chih

During the late Han Dynasty and the Wei and Jin Dynasties, almost every scholar could write Tsao Shu. The royal members of the Jin Dynasties were even writing letters in Tsao Shu and exchanged their insights and skills. Those royal calligraphers included Wang Hsi-Chih ( 王 羲 之 ), Yu Yi ( 庾翼 ), Wang Hsian-Chih ( 王 獻 之 ), Hsieh An ( 謝 安 ), and so on. Thus, Tsao Shu took a quantum leap in the Jin Dynasty.

Tsao

Style works by Wang Hsi-Chih

In

the Tang Dynasty, both Zhang Shui ( 張

旭

) and Huai Shu ( 懷

素

) liked to write

calligraphy after getting drunk. They would yell, stride, and show weird

behaviors during their creation. They were peered as “Crazy Zhang & Weird Monk 張

顛

狂

僧.”

They established a Tsao Style commonly referred as Wild Cursive "Kwun Tsao

狂

草

”

(“Kwun” means crazy and bold.)

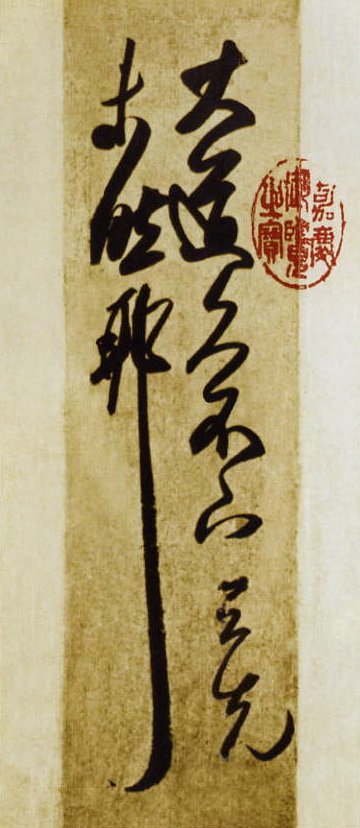

Huai

Su’s Autobiography (Click for complete picture)

From the Han Dynasty to the Tang Dynasty, Tsao Shu had three major changes in

styles and structures. The way a character was written in Tsao Shu was already established in

the Han Dynasty; the following changes in the Jin and Tang Dynasties were only

for the strokes and character structures for the sake of art. So there are three main styles of Tsao

Shu: Zhang Tsao ( 章

草

), Jin Tsao (今

草

), and Kwun Tsao (

狂

草

).

In early 1900s, Yu You-Ren ( 于 右 任,1879-1964) promoted standardized Tsao Shu due to the drastic irregularities and differences between each Tsao Shu calligrapher and character in different dynasties. He founded the “Society of Standardization of Tsao Shu.” He studied ancient calligraphy works in Tsao Shu and revitalized and promoted Tsao Shu to the modern society based on the four principles - “easy to read, easy to write, accurate, and beautiful.”

Among

the five major styles of Chinese calligraphy, Tsao Style is probably the most

difficult due to technical requirements and foundation. Only after one has mastered Kai

and Hsin Styles can he or she begin to learn Tsao

Style. A lot of calligraphy teachers prefer students to start from Jin Tsao ( 今

草

). A proper sequence of learning is very important to build a good foundation.

Since

the sidepiece or radical (“Bu So 部

首

”),

derivatives, alternatives, borrowing, mixture, and various rules can be very

confusing, a student may resort to Tsao Shu manuals or dictionaries to better

understand the writing principles and avoid errors. A beginner may choose to

start from “The 1000 Characters in Tsao Shu

草

書

千

字

文”

by Zu Yong ( 智

永

), Huai Su (

懷

素

) or other calligraphers.

Click

for a list of recommended readings in Chinese: Reference

1

Reference

2

Reference

3

After

the student has mastered the rules, requirements, structures, stroke sequences,

and connections between several characters, s/he may proceed to Kwun Tsao or

Zhang Tsao from Jin Tsao.

Please also remember the Center Tip Theory “Zong Fon 中 鋒 理 論 ” (literally, brush pen tip at the middle of hairs) is very important for Jin Tsao and Kwun Tsao writing. It was mentioned by every prominent calligrapher. When Yen Jen-Ching stated how his teacher Zhang Shui passed to him the secrets of using a brush, he pointed out that a calligraphy stroke should look like drawing on sand with awl (“Zuei Hwa Sa 錐 劃 沙.”) The principle requires keeping our brush handles and brush hair as straight and vertical as possible. It’s different from painting or the Western way to hold a pen. According to this principle, we should never ever bend the brush handle and the hair. We may rotate the brush when necessary with fingertips (knuckles not recommended). Bending a brush outward, sideways or toward oneself is a very common defect and is seen among laymen. By strictly obeying this principle, the hairs (or the sharpness of hairs) of a brush are hiding inside during brush motions rather than going scattered and collapsed.

Du

Du (?-?)

杜

度

He

was allowed to present reports to the Emperor Zhang (

漢

章

帝

) in running style calligraphy. Thus his Tsao Style was

called “Zhang Tsao 章

草.”

Even the King of Tsao Style, Zhang Chih, admitted that his work was inferior

to Du Du’s and Tsui Yuan’s works.

Tsui

Yuan (77-142)

崔

瑗

He was good at Zhang Tsao. His book "Tsao Shu Postures 草 書 勢" was valued by later calligraphy theorists. His Tsao Shu was not as ingenious in structures as his teacher Du Du but was more charming than Du Du's. He was peered with Du Du. His style was masculine and vigorous.

Zhang

Chih (?-193)

張

芝

He won the title ”King of Tsao Shu 草 聖.” He practiced calligraphy by a pond and it became black because he washed his brushes and ink plate there. He studied Zhang Tsao from Du Du and Tsui Yuan and then established the modern style of Tsao Shu. He had a great influence on Wang Hsi-Chih and Wang Hsiang-Chih.

Wang

Hsi-Chih (303-361)

王

羲

之

He

earned

the titles of "The King of Calligraphy 書

聖"

&

"The Dragon of Hsin Shu 行

書

之

龍.

快雪時晴帖

(http://www.xys.org/piclib/kxsq.html)

Wang

Hsian-Chih (344-386)

王

獻

之

The 7th son of Wang Hsi-Chih. He studied his father's calligraphy earlier and studied Zhang Chih's calligraphy later. He reformed bravely. His style was brilliant and heroic.

Sun

Guo-Ting (684-702?)

孫

過

庭

Famous Tsao Shu calligrapher and theorist in the Tang Dynasty. He inherited the Two Wangs’ method. His work shown here ( 書 譜 ) is an important essay about Tsao Shu.

(http://www.geocities.com/Vienna/Studio/5810/p1n.html)

Zhang

Shui (?-?)

張

旭

He also won the title "King of Tsao Shu 草 聖" after Zhang Chih. Every time he was drunk, he was inspired and did a terrific work. He was nicknamed “Crazy Zhang.” Zhang Shui's calligraphy, Lee Bai's poem, and Pei Ming's sword playing were the “three exquisite talents in the Tang Dynasty”. Zhang Shui was a nephew of Lu Jian-Chih’s son. Lu Jian-Chih ( 陸 柬 之 ) was a nephew of Yu Shi-Nan ( 虞 世 南 ). From the family lineage, Zhang Shui inherited the secrets and system from Tsui Yuan, Zhong Yao, Wang Hsi-Chih, Wang Hsian-Chih, and Yu Shi-Nan; however, he represented calligraphy strokes in a brand-new look and invention. His followers included Hsu Hao, Yen Jen-Ching, and Tsui Miao.

Huai

Su (725-785)

懷

素

He became a monk at ten years old. He was very fond of wine, just like Zhang Shui. He would write beautifully and quickly whilst he became drunk and inspired. His calligraphy was like a running snake or a flying dragon and also resembled strong wind, violent storm and thundering. His Tsao Shu was peered with Zhang Shui’s. He called his writing "The calligraphy of an intoxicated immortal." He was highly regarded by Yen Jen-Ching, Lu Xian and Zhang Wei. Being very poor, and lacking money to buy paper, he planted many banana trees in his backyard and used the leaves for practice. It is said that he practiced so hard that he had piles of bad brushes like a tomb and most of his banana leaves were black.

Free Download (http://www.9610.com/huaisu/qzw.htm)

Xien-Yu

Su (1257-1302)

鮮

于

樞

He studied Zhang Tien-Si’s work first, then Jin & Tang Dynasties’ calligraphy to establish his style. Inherited the Two Wangs’ spirit.

PLEASE CHECK BACK LATER.

Most

Chinese calligraphers agree that a beginner in Tsao Style starts learning Jin Tsao

before Kwun Tsao and Zhang Tsao. Each of them has unique underlying principles

to write a character. However, Kwun Tsao is more metaphysical and abstract and

looks crazy. It sometimes does not follow strictly the rules and principles as

set by Jin Tsao. However, this does not mean one can create his own way of

writing a Tsao Shu character randomly without following any rules. If so, there

will not be any standard to appreciate each other's work and achievement.

We

may learn more broadly and deeply by collecting and appreciating ancient

masterpieces. From analyzing each

masterpiece and master, we may eventually realize their learning sources,

creation processes and why their immortal works have remained famous for

thousands of years. Learn and we will know our insufficiency; study abroad then

we may specialize.

Center

Tip Theory 中

鋒

理

論

–

Holding a brush vertically but not bent; never let hairs collapse.

Jin

Tsao 今

草

–

Founded by Zhang Chih in the Han Dynasty.

Kwun

Tsao 狂

草

–

Founded by Zhang Shui in the Tang Dynasty.

Yi

Zuo Yang Yu 抑

左

揚

右

–

Simplify left sidepiece and focus on right sidepiece in a Tsao Shu character.

Zhang

Tsao 章

草

–

Founded by Du Du in the Han Dynasty.

Appendix: More calligraphy

works in Tsao Style

Sun

Lu-Tang (1861–1933)

孫

祿

堂

Famous Ba Gwa Zhang and Hsing Yi Chuan martial artist. Founder of Sun Style Tai Chi Chuan. At his youth, he learned to make calligraphy brushes from his relatives. Later, he gave up making brushes and devote himself to martial arts. He was the very first person to publish books of Chinese internal martial arts theories.