Principles of Chinese Calligraphy

|

臨帖前先靜心讀帖,了解用筆及筆劃切入的角度、收筆的方法、結構的密疏度,甚至原帖作者 臨與摹何者為先?

|

§ 9.1 – Emulation Is An Indispensable Way to Learn Chinese Calligraphy

Emulation of Chinese calligraphy masterpieces is somewhat similar to martial artists doing forms and learning from their masters. The forms or masterpieces are the prototype for learning and a self-correcting path that should be observed throughout the entire life of an artist. There is absolutely no exception in Chinese calligraphy. All the masters of Chinese calligraphy are lifetime students of Lin Mo.

All

great Chinese calligraphers went through a long time in their life emulating

previous calligraphers’ works. This might take up to 20 to 50 years. Have we

ever bought a Form Book (or Copy Book) or a masterpiece accomplished

by a calligrapher before age 35? Not in Chinese history! All of Wang Hsi-Chi’s

masterpieces we see today were done after he reached 40. The other calligraphers left us

a huge treasure of masterpieces that were all done after 40 years of age, mostly

during 45 to 65 years old in which this period was considered to be the prime. All of these depend on the artist’s skill level, insight, knowledge in

all fields, moral standards, and spiritual growth. There is absolutely no shortcut in learning

Chinese calligraphy and emulating masterpieces is indispensable to become a good

Chinese calligrapher.

The

processes of learning Chinese calligraphy can generally be summarized into four stages:

Observation “Guan”

觀

Emulation “Lin Mo” 臨

摹

Comprehension

“Wu”

悟

Creating new styles “Tsung” 創

§

9.2 - Definition of Lin Mo (Emulation)

The

Chinese term “Lin Mo 臨

摹

”

actually contains two processes: “Lin

臨”

and “Mo

摹.”

“Lin” means to observe the writings in a Copy Book, masterpiece, or

teachers' writings and then transfer onto the paper during practice. “Mo”

means to trace other’s writings and then fill up the trace. Today the two

processes may be used to refer to practicing or copying a calligrapher’s work.

Zhang

Chih (

張

芝

) used to practice “Lin Mo” and calligraphy by a pond. He washed his

brushes and ink stone there and the pond became all black. Later calligraphers like

Wang Hsi-Chih may have followed this tradition by practicing calligraphy near a pond or

a river. So “Lin

Mo” is also called “Lin Tsu

臨

池

”

("Tsu" means a pond.)

Lin

Mo is not just copying or mimicking the shape, position, and structure of each

character in a calligraphy work. It has many, many levels of meanings and

applications. The deepest level is

to inherit the spirit and soul of the work, not just the appearance. Thus I prefer

to use “emulation” and “Form Books”

instead of "copy" and "Copy Books" as translated in most English resources about Chinese

calligraphy for the practice of Lin Mo.

§ 9.3 - How to Lin Mo

For a beginner, Lin Mo can be done with a trace sheet “Miao Huong 描 紅 .” Besides filling in the blanks for each stroke, the students also have to pay attention to the operating techniques mentioned in "Principles of Operating A Brush" and "Center Tip Theory." Otherwise, Miao Huong is just copycat, not practice.

Nowadays students focus more on “Lin” so the “Mo” process has been neglected. The following are some trace sheets I created for practice using a scanner and a computer. They are more convenient and help us better position each stroke correctly. By using “Lin” and “Mo” interchangeably, we can make more progress than just using “Lin.” "Mo" sometimes help the student "feel directly" the original master's emotion better than "Lin."

Most Chinese calligraphers agree that there are two ways or stages of

Lin Mo. The first way (

臨

形 )

is to focus on the shape of structure and position of strokes of every

character. The practitioner tries to mimic the appearance and then the spirit

will show. If one focuses too much on appearance, he will lose the essence and

spirit. The second way (

意

臨 ) is to focus on inheriting

the spirit but not the appearance. A Lin Mo work using the second method may

look similar in spirit but not necessarily similar in appearance.

For

the first method, we have to analyze the characteristics of the work before we

start. If we just grab a brush and paper and start mimicking, this will not help

us make progress. The first step in practicing Chinese calligraphy is not the

brush or hand. It’s the mental – emptying one’s mind. That’s why it’s

also called Heart

Painting ( 心

畫

).

For musicians, before they start playing, they have to discern the

characteristics of a composition. Be it happy, romantic, heroic, spirited,

melancholy… So a musician won’t play a Chopin nocturne as a heroic Beethoven

symphony.

Correct interpretation of an artwork is as important as the creating process. In Lin Mo, try to ask in our heart honestly and thoroughly the following basic questions and our goal will be clear.

Do I know the name of

the calligrapher and style? In which dynasty? What was the calligraphic and

historical background at that time?

What are the main

characteristics of the work?

How does each character

look like? Is it short or tall? Thin or think? Solemn or relaxed? Smooth or

stable? Big or small? Exaggerated or depressed? …

How did the

calligrapher start the first stroke? Did he use Zong Fong, Tse Fong, with or

without Tsun Fong? How did he end each stroke?

How did each stroke

contribute to the structural design of a character? Is it upright or

slanted?

What is the length of

each stroke? Distances between strokes? Degrees of angles? Turnings?

How are the spacing and

rooms arranged between the strokes, characters, and lines?

If there is connecting

between several characters, is it implied or physically observable? Am I

able to achieve this? How?

Overall, have I emptied my mind to accept the calligrapher’s work humbly? How do I overcome self bias? Try to realize the fact that there is a long history of China and why this calligrapher’s work is handed down as a norm for us to emulate.

|

臨形步驟 臨帖分臨形與臨意 悟「理」而遺「文」,猶得魚而忘筌也。惟無書法根基者,初學仍應由臨形入手為宜。

|

The

second way of Lin Mo is inheriting the spirit of the work, not the appearance.

It’s called “Yi Lin

意

臨 .”

Yi means mind or intention. It’s a very dangerous stage of practicing. One

might end up worthless if he is overly self biased and not having enough self

awareness!

Yi Lin is a more metaphysical method than the first method. However, without going through a long Lin Mo process with the first method, no one can inherit and match the spirit and essence of the original work with the second method. The first method sets the standard “as is” and the second method focuses on “substance over form.” Without the essential forms we cannot create substance – there will be substance over nothing and it’s not even substance – it’s just ego and self-indulgence and obsession.

|

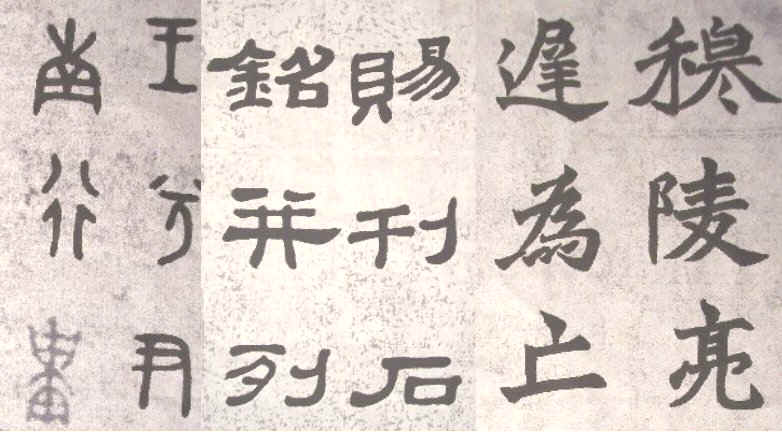

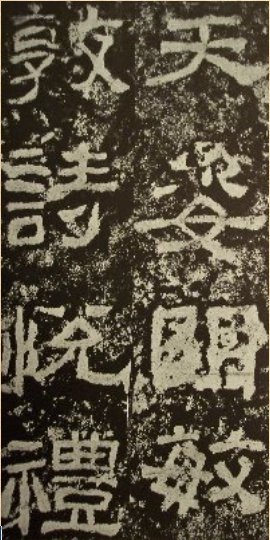

Stone Drum Inscriptions (original) |

Yi Lin by Wu Tsun-Shuo |

Emulation “as is” |

When

a Chinese calligraphy student is doing Lin Mo practice, one has to realize that

a good musician interprets a composer’s work with his / her sincerity, fidelity, and

then insight. If an instrumentalist can do “full justice” to a composition,

s/he may add what s/he intends to impress the audience – only after s/he has

done “full justice.” A “full justice” attitude in Lin Mo means that the

student needs to “duplicate the original masterpieces” to the greatest

extent and nuances. If you choose to be serious about Chinese calligraphy, you

may remember almost all ancient master calligraphers like Wang Hsi-Chih and Mi Fu could

“duplicate” the original masterpieces so well that the average viewers could

not distinguish the difference.

Nowadays

many calligraphers publish albums of their own works and emulated works. Some of

their emulated works contain no substance, form, appearance or even basic

Chinese calligraphy principles. Some even publish books that say those

masterpieces (“Fa Te 法

怗

”,

Fa means method, Te means Form Books or masterpieces) are not the end, just the

process – and this is true. Almost any forms of art emphasize on creating a

personal style. So does Chinese calligraphy. But without humbling and emptying

one self, no one can inherit the true essence of Chinese calligraphy and then

create an elegant style that is accepted by serious artists. Without learning,

anyone can do what s/he intends and no one will appreciate each other’s work.

However, not all of preexisting norms set by ancient masters can rule forever.

Some can be revolutionized and changed boldly only by later artists who have

matured in their skills, mentality, moral, and insights.

The following anecdote in Chinese and English may give us a hint as how a serious Chinese calligraphy student can spend his / her effort in the Lin Mo practices. The phenomenon of "synesthesia" is a realm of scientific study.

|

孔

子

學

琴 |

|

這一天,師襄子教完了一支樂曲,要他獨自練習十天,然后再教新曲。可是十天過去了,孔子仍然埋頭苦練老曲子,似乎把學新曲的事忘記了。師襄子提醒他說:“你已經把這首曲子彈熟了,可以另學新曲了。”孔子卻說:“不行啊,我只是剛剛把音律彈熟,技法還很生疏哩!”

又過了幾天,師襄子說:“你的技法熟練了,可以學新曲了。”不料孔子又說:“不行啊!我還沒有明白它的內容呢!這不能說是真會。”于是又埋頭彈起來。

再過了好幾天,師襄子又提醒他說:“好啦,你不僅熟悉了它的音律、技法,連它的內容也明白了,可以彈新曲子了!”孔子仍然搖頭說:“不行呀,我依然算不得真會,我還沒有體會到作曲者的為人呢!”

師襄子覺得言之有理,也就不再催促他練新曲了,只是耐心的等待著。

時間又過去了好幾天。這一天,孔子正埋頭彈琴,彈著,彈著,忽然抬起頭來兩眼閃爍著喜悅的光芒。他對師襄子說:“好啦,我知道作曲家是怎樣一個人了!這個人高高的個子,黑黝黝的臉,眼睛炯炯有神,是個具有王者氣質的人。莫非這曲子是周文王所作?我想除了他,別人是作不出這樣好的曲子來的!”

師襄子不禁大驚,恍然醒悟道:“若不是你今天這一說,我倒把這一切都忘記了。是呀,很久以前,我的老師曾經對我說過這首曲子叫《文王操》,它的作者是周文王。”

師襄子對孔子佩服不已,身不由己地躬身相拜。孔子急忙回禮,說:“我現在可以學彈新曲了!” Confucius Studies

the Qin Confucius

lived during the Spring and Autumn Periods and was a great

statesman, educator, and thinker. He liked singing, music composition. He

also could play the drums, Chinese zither and several other

musical instruments. For a period of time, Confucius studied the

seven-string Qin (musical instrument) with Lu Country's musician Shi-Hsian

Tzu. One

day, Shi-Hsian Tzu taught him a tune and wanted him to practice alone and

then teach him a new tune afterwards. Ten days later Confucius still

practiced so diligently the first tune that he forgot to study the new

tune. Shi-Hsian Tzu reminded him of this and said: "Your have

perfected the first tune I gave you and therefore I gave you a new

tune to study." Confucius replied: "I am not good at it.

I barely understand its meaning and my technique is not polished!” Several

days later, Shi-Hsian Tzu said: "Your technique is excellent;

therefore, I give you a new tune to study.” Confucius interrupted

and said: "It is not good! I have not understood its content! I

cannot say that I understand its meaning." Confucius started to

practice hard again. Several

more days passed and Shi-Hsian Tzu pointed out to Confucius: “Your

execution of the song is good. You not only have understood its

mood, the technique and its intent. Therefore I approve that you

learn a new song.” Confucius still shook the head said: “It’s

still not good enough. I still think that I have not understood its

meaning and I have not understood the composer’s personality!"

Shi-Hsian Tzu, who did not previously admire Confucius bowed to him without reservation. Confucius rushed to say: “Now I must not delay to study a new tune!"

|

§

9.4 – Calligraphers’ Conscience

For

those calligraphers that don’t appreciate the value of ancient masterpieces,

they cannot do a good emulation work – not in strokes, character structures,

and spirit. Oftentimes they will try to publish or talk like that they are using

the second method (“Yi Lin”) to inherit the spirit instead of the appearance

to disguise those who have never learned calligraphy and lie to themselves. Woe!

For

calligraphers with a little bit more awareness and appreciation, they will try

to insert their own preferences or formulas into each stroke of a character that

has different styles, spirit, appearance, structure, or operating methods. And

they still proclaim they have gone through the first process and are using the

second method to inherit the spirit rather than the appearance. For example,

this group will typically insert Tang Kai strokes in emulating Wei Bei Kai

Style. Those two styles are totally different in spirit and essence. (Please

refer to Resurrection

of Wei Bei in the “Kai Style” section.)

For

calligraphers with better awareness and appreciation than those two groups

above, they know they should avoid the mistakes by those groups but they cannot

get rid of them at first– they are struggling. At least they are struggling

for the right path but cannot find a way. As they realize their imperfection and

deficiency, they are heading for a higher level of art. They keep searching the

Way in life and practice and keep growing. They realize that they can never

reach the perfect level of ancient Chinese calligraphy masters. The more they realize this, the more

they become humble and reach a higher level. And finally their creation of

personal styles will be regarded seriously and remembered.

§

9.5 – Calligraphers’ Confession

In all stages of Lin Mo, serious calligraphers will constantly ask themselves “How much Yi (mind) of themselves is close to the original masterpieces?” They will also continuously remind themselves “Don’t let Yi Lin be an excuse to neglect the shape, structure, nuances and details of the original.” If we are not aware of these questions, practice can destroy its purpose and lead us astray without self-awareness. A lot of Chinese calligraphers adopt the famous saying “Form Books are just a way, not an end of methodology” ( 法 帖 只 是 法 門, 非 法 海 也 ) as a self-defense and disguise for their lack of Lin Mo achievements. Please don’t use this famous saying to cover our inner deficiency.

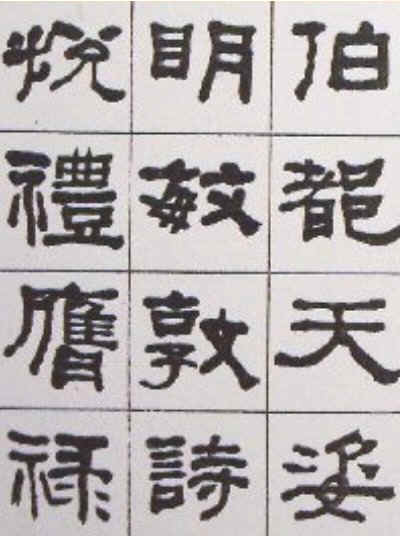

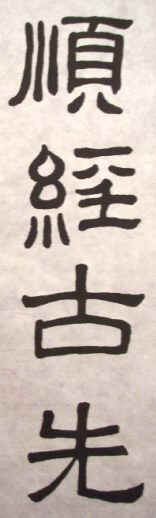

Xi Hsia Sung (original) |

Yi Lin by Ho Shao-Ji |

original |

Emulation “as is” |

§

9.6 - How to Overcome Failure Strokes in Emulation

A

failure stroke “Bai Be

敗

筆

”

is one that is not satisfactory or desired. It is a disaster or accident due to negligence, incompetence, rush or mindlessness.

To

avoid a failure stroke, we must

not make indecisive strokes – not knowing how we are going to write the

strokes and where they are leading to. So mental preparation plays an

indispensable role in executing a successful stroke.

Every

musician plays wrong notes in his or her lifetime. And even master calligraphers

sometimes render a failure stroke. Some failure strokes may be forgiven; some

will destroy the whole work depending on the severity. Amending

a failure stroke (“Miao

描

”)

is considered cheating in Chinese calligraphy. It’s forbidden for all students

and calligraphers. It’s a stumbling block to progress and success. If we make

some failure strokes, accept the fact and continue the work. Start over next

time and pay more attention by focusing more deeply. Or we can practice that specific

stroke over and over again to avoid reoccurrence.

In contrast to Western calligraphy, dry brush strokes are viewed as a natural impromptu expression rather than a fault or failure stroke. While Western calligraphy usually pursue font-like uniformity, homogeneity of characters in one size is considered only a craft in Chinese calligraphy.