透視學 Perspective

Updated : 2012-03-31

透視可分為:線透視、散點透視、空氣透視、隱沒透視。

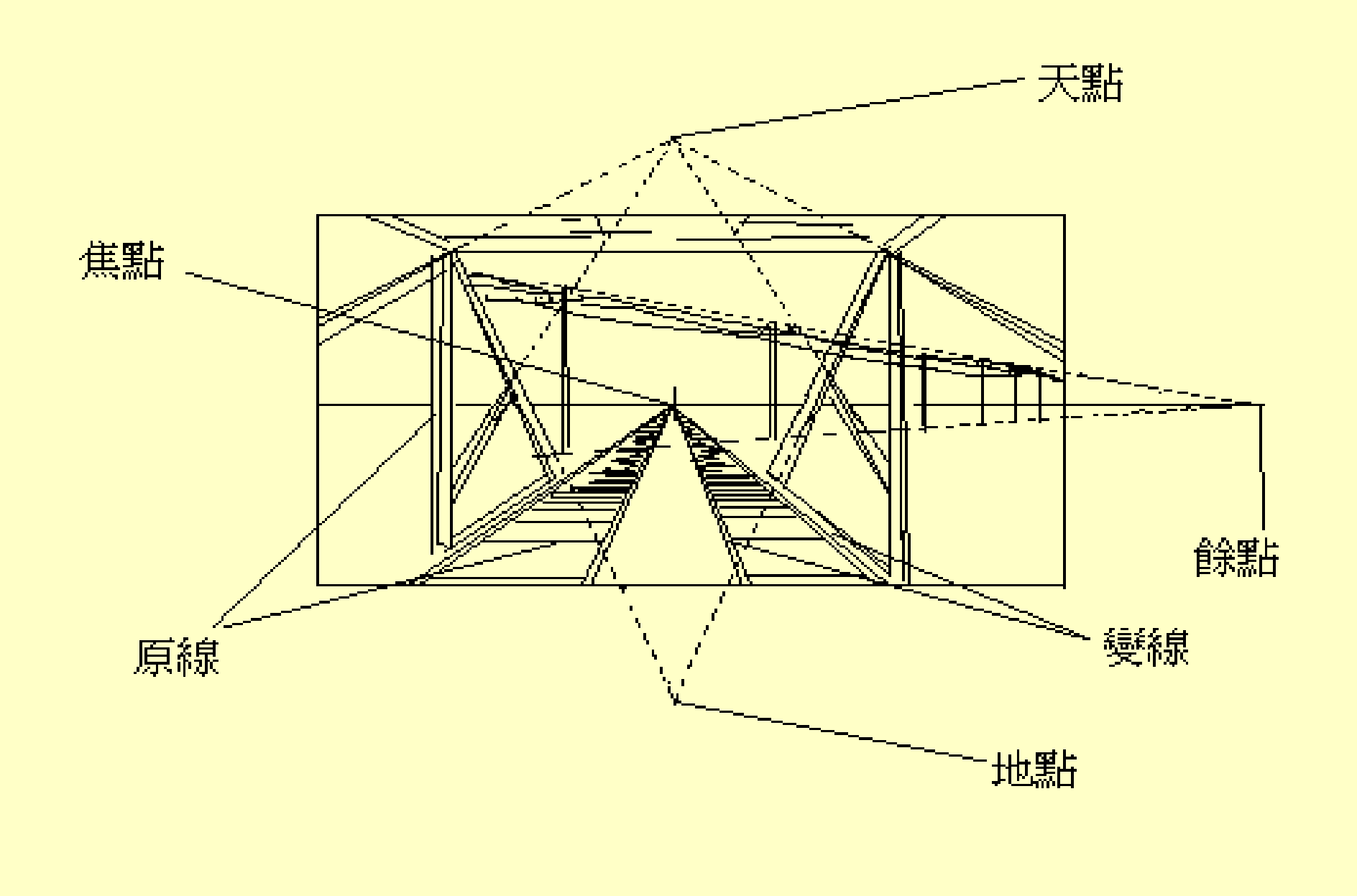

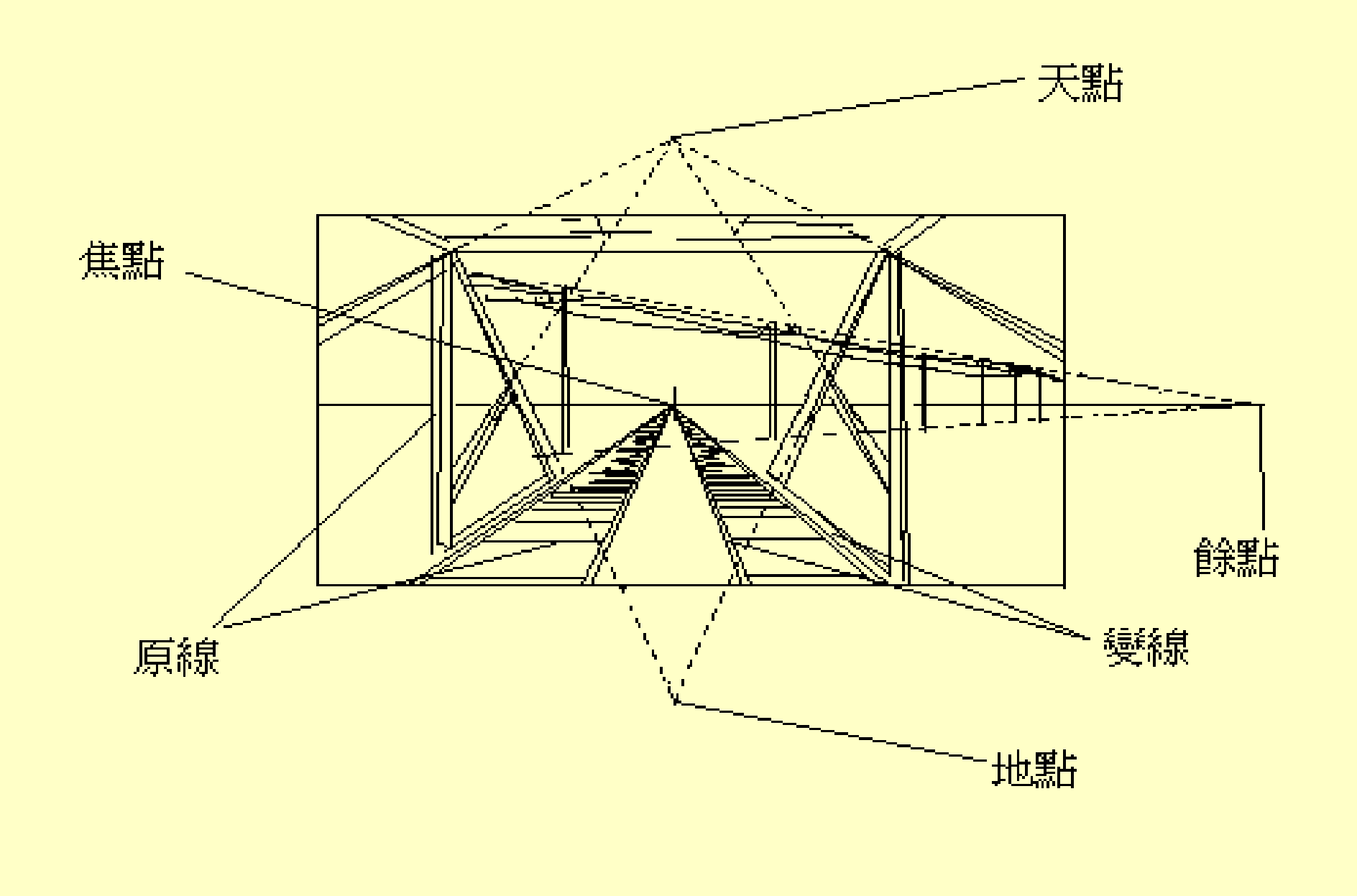

線透視

線透視是一種把立體三維空間的形象表現在二維平面上的繪畫方法,使觀看的人對平面的畫有立體感,如同透過一個透明玻璃平面看立體的景物。透視畫法要遵循一定的規律及幾何學要素:

原線:和畫面平行的線,在畫面中仍然平行,原線和地面可以是水平、垂直或傾斜的,在畫面中和地面的相對位置不變,互相平行的原線在畫面中仍然互相平行,離畫面越遠越短,但其中各段的比例不變。

變線:不與畫面平行的線都是變線,互相平行的變線在畫面中不再平行,而是向一個滅點集中,消失在滅點,其中各段的比例離畫面越遠越小。

滅點包括四種:

焦點 - 是作畫者和觀眾看的主要視點,與地面平行,與畫面垂直的線向焦點消失。

天點 - 畫中近低遠高的,與地面不平行的線都向天點集中消失,天點和焦點在同一垂直線上。

地點 - 畫中近高遠低的,與地面不平行的線都向地點集中消失,地點和焦點在同一垂直線上。

餘點 - 與地面平行,但與畫面不垂直的線向餘點集中消失,餘點有許多個,和焦點處於同一水平線上,每個和畫面不同的角度都有一個不同的餘點。

當畫家平視時,焦點和餘點都處於地平線上,仰視圖焦點向天點靠攏,俯視圖焦點向地點靠攏,餘點始終和焦點處於同一水平線上。

散點透視

(Cavalier Perspective, Multi-Point Perspective, or Multi-Vanishing

Point

Perspective)

西方繪畫只有一個焦點,一般畫的視域只有60度,就是人眼固定不動時能看到的範圍,視域角度過大的景物則不能包括到畫面中,如同照相。中國畫則運用散點透視法,即一個畫面中可以有許多焦點,如同一邊走一邊看,每一段可以有一個焦點,因此可以畫非常長的長卷或立軸,視域範圍無限擴大。

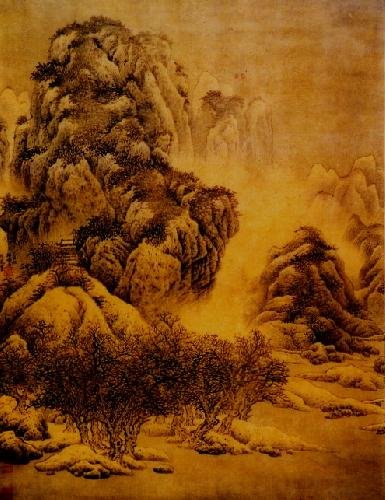

中國山水畫特殊觀念散點透視中有三遠: 平遠、深遠、高遠 (宋朝以後增列第四遠-闊遠)。

空氣透視

用顏色的鮮明度的大小表現物體的遠近,近處物體色彩鮮明,越遠的物體越失去原來的顏色。

隱沒透視

用物體清晰度的大小表現物體的遠近,所謂「遠山無皴,遠水無波,遠樹無枝,遠人無目」。

Definitions

of Perspectives

因此可以畫非常長的長卷或立軸,視域範圍無限擴大。

自然界的山光水色,總是讓人們感動莫名,也給予藝術家無盡的創作題材。但是當你觀賞一幅中國山水畫時,應該怎樣與古畫對談,進入畫中,了解畫家所要傳達的意念呢?他們又怎樣在平面的畫布上表現空間感呢?

北宋有個畫家郭熙,由於熱愛遊歷林木山泉,加上用心觀察,因而體悟呈現出國畫特殊的視點,他提出「高遠」、「深遠」、「平遠」的三遠法,大不同於西方繪畫定點單一的透視方式。

從山下仰望高聳的山巔,就是「高遠」;「深遠」是把山石前後或斜向推展,加強空間的深入感;「平遠」則是將山水景物向左右水平伸展,形成空間開闊的效果。

「三遠法」除了透視功用外,還有一個作用是營造意境,隨著三種視點的不同,意境的表達也有所差別呢﹗

How do I achieve the "rolling frame" >>> HELP?

<iframe src="c:/art-virtue.com/painting/techniques/perspective/scroll-horizontal-1.jpg" width="98%" height="326" frameborder="0" margin="0"></iframe>

中國山水畫特殊觀念散點透視中有三遠: 平遠、深遠、高遠 (宋朝以後增列第四遠-闊遠)。

畫面中,畫家的視角是隨意移動的,因而產生了多個消失點,這叫作散點透視。這樣,畫家可以打破空間的局限,從多個角度描繪客觀景物,畫家和欣賞者就像坐在船上,景物隨著船的移動而移動。

very fat horse hips

Pei Shio?? characters triangle to pyramid

that Taoist painting changing Yuan Dynasty ? multi dimensions

Book of Changes

Multi-point attacks of Bagwa insert YouTube

does not aim at targets at opponent's front; Dong Hu-Ling

Yixing teapots

Polyphony Godowsky after Chopin etudes

YouTube original vs. Hamelin

Certain path of Qi or wholeness With/Without Yi Real Yi

TCM not focused on one problem

中國繪畫和西方繪畫一樣都講求畫面的透視效果,所不同的是西方畫家的透視是焦點透視,也就是說,畫中只有一個視點(即人的視角)和一個消失點,這是符合人類觀察自然界的實際狀況的。而中國繪畫>>>并非如此,它有許多個消失點,畫面中,畫家經常以大觀小的構圖方式、散點透視法與鳥瞰式的表現方法,來創造水墨畫,其視角是隨意移動的,因而產生了多個消失點,這叫作散點透視。這樣,畫家可以打破空間的局限,從多個角度描繪客觀景物,畫家和欣賞者就像坐在船上,景物隨著船的移動而移動。由於中國畫家有很高的審美水平,懂得用這種技巧,因此可以將千里的江山,全部表現在一幅畫之中!

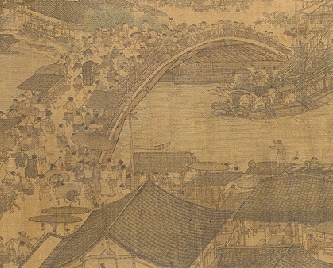

以《清明上河圖》為例,作者以散點透視法,也就是以不斷移動視點的方法,來表現豐富的環境景觀與人物活動情況,造成了類似連環圖畫的效果!

所謂的散點透視法,就是華夏民族,以不表現定點式的觀察、不表現具體光線所製造的時間、不表現固定視線内的有限空間等方式,來進行作畫;散點透視法,是一種符合心理的真實,也就是内在真實的方式,這比西方焦點透視法,著重視覺與外在的真實,更高明!這就是中國畫家過人之處。

散點透視法符合心理的真實,是种內在的真實。焦點透視法符合視覺的真實,是种外在的真實。這兩种結构法的差异,從文化積淀角度看,也許正透露出了一者更重視內心(主体),一者更重視環境(客觀)的東西文化差异的消息。

在一般人的印象中,認為只有西洋畫有透視,傳統的中國畫沒有透視。這是不符合事實的。傳統的中國畫是有透的但它的透視方法与西洋畫的透視方法有很大的不同,西洋畫講究焦點透視法,傳統的中國畫講究散點透視法。所謂焦點透視法,就是嚴守一個特定的視點去表現景物,近大遠小,呈放射狀。散點透視法不拘泥于一個觀點,它是多視點的,在表現景物時,它可以將焦點透視表現的近大遠小的景物,用多視點處理成平列的同等大小的景物。散點透視法,可以比較充分地表現空間跨度比較大的景物的方方面面,這是傳統中國畫的一個很大的优點。

例如宋代張擇端的《清明上河圖》長卷,它用散點透視的多視點原理,把古代汴京東郊以虹橋為中心的風景、人物、城郭、街道、橋梁。船只等等丰富內容的場面散點在一個畫面,給予了充分詳盡的表現。如果采用西洋畫的焦點透視法,它只能突出地表現畫家确定的一個視點周圍的景物,也只能將其它許多景物根据近大遠小的原則虛隱掉。

傳統的中國畫并不是不重焦點透視,它不過是在一幅畫中根据需要采用多個焦點透視而已。這是傳統中國畫區別于西洋畫的一個重要特點。中國古代确實沒有系統的透視學,但對于科學的焦點透視法,也早有朴素的深刻認識。早于德國透視畫家丟勒一千多年的六朝劉宋時期的宗炳,就曾寫過一篇《畫山水敘》說明了透視學中按比例遠近布置物景的法則。但中國畫家多喜歡表現空間跨度大的山川江河,甚至想把整條長江都畫到一幅畫中,他們不滿足于用一個焦點來束縛自己的視野,因此,中國畫家多采用移動式、減距式、以大觀小的散點透視法來表現無限丰富的景象。這种手法給畫家帶來了空間處理上的极大自由度。

散點透視 從清明上河圖看中國繪畫的空間處理

中國繪畫中散點透視的運用,最著名的畫作是北宋張擇端的清明上河圖卷,這是中國繪畫史上最為杰出的藝術精品。其偉大之處在于它表現的場景最開闊,畫面內容最丰富,描繪的人物最多。畫家以散點透視的手法把綿延几十里的首都城內外的景象展現于五米多長的畫幅里,這在西方繪畫中是無法實現的。該圖涉及到宋代社會的各個方面,如商業經濟、交通運輸、城市建設、文化娛樂等等。張擇端在圖中繪有各行各業、各种等級的人物共500余人,各類牲畜50余頭,車、轎20余輛,舟船20多艘,店鋪百余家,所繪宋都汴京在清明時節中的市相百態,場景之大,人物之眾,亦為世界繪畫史之最。

《清明上河圖》卷,北宋,張擇端作,絹本,淡設色,縱24.8cm,橫528cm。

《清明上河圖》描繪的是清明時節北宋都城汴京(今河南開封)東角子門內外和汴河兩岸的繁華熱鬧景象。全畫可分為三段:

首段寫市郊景色,茅檐低伏,阡陌縱橫,其間人物往來。

中段以上土橋為中心,另畫汴河及兩岸風光。中間那座規模宏敞、狀如飛虹的木結构橋梁,概稱虹橋,正名上土橋,為水陸交通的匯合點。橋上車馬來往如梭,商販密集,行人熙攘。橋下一艘漕船正放倒桅杆欲穿過橋孔,梢工們的緊張工作吸引了許多群眾圍觀。

后段描寫的是市區街道,城內商店鱗次櫛比,大店門首還札結著彩樓歡門,小店鋪只是一個敞棚。此外還有公廨寺觀等。街上行人摩肩接踵,車馬轎駝絡繹不絕。行人中有紳士、官吏、仆役、販夫、走卒、車轎夫、作坊工人、說書藝人、理發匠、醫生、看相算命者、貴家婦女、行腳僧人、頑皮儿童,甚至還有乞丐。他們的身份不同,衣冠各异,同在街上,而忙閒不一,苦樂不均。城中交通運載工具,有轎子、駝隊、牛、馬、驢車、人力車等。 車輛有串車、太平車、平頭車等諸种,再現了汴京城街市的繁榮景象。高大的城門樓名東角子門,位于汴京內城東南。

全卷畫面內容丰富生動,集中概括地再現了12世紀北宋全盛時期都城汴京的生活面貌。

此畫用筆兼工帶寫,設色淡雅,不同一般的界畫,即所謂別成家數。构圖采用鳥瞰式全景法,真實而又集中概括地描繪了當時汴京東南城角這一典型的區域。作者用傳統的手卷形式,采取散點透視法組織畫面。畫面長而不冗,繁而不亂,嚴密緊湊,如一气呵成。畫中所攝取的景物,大至寂靜的原野,浩瀚的河流,高聳的城郭;小到舟車里的人物,攤販上的陳設貨物,市招上的文字,絲毫不失。在多達500余人物的畫面中,穿插著各种情節,組織得有條不紊,同時又具有情趣。

后幅有金張著、明吳寬等13家題記,鈐96方印。

《清河書畫舫》、《庚子消夏記》、《式古堂書畫記》等書著錄。

中國最早在南北朝時代就已經有畫家提出了原始的透視原理,之所以後來沒有被採用,實際的原因是覺得標準的透視對繪畫的束縛太大,所以寧可放棄這種對景物的複製,而採用來散點透視法自由地表達繪畫的意境。

清代畫家鄒一桂 (not 鄒一枝 ???) 從中國畫的構圖特點出發,分析了西洋透視及光暗原理,他認為中國畫不宜全採用,只能參用其一二,他說:""西洋人善勾股法,故其繪畫于陰陽遠近,不差錯黍,所畫人物,屋樹皆有日影",他認為"布景由闊而狹,以三角量之。畫它室于牆壁,令人凡欲走進,學者能參用一二,亦具醒法,但筆法全無,雖工亦匠,不入畫品。"因而中國畫所採用的透視,仍然保持著用散點透視法作畫。

這點反映出東西方文化的差異,西方崇拜理,講求客觀,自然是什麼樣子就做成什麼樣子,世界是什麼樣子就是什麼樣子,不能改變,這種方法看似謙虛,其實卻是把自己割裂在自然以外的一種做法,很容易陷入到狂妄的境地去;而東方文化在客觀觀察了自然再加上自己的感受,世界的樣子是我觀察總結的樣子,表面上似乎很自大但是卻是把自己也算做自然的一份子溶入自然的做法。 >>> Add to Intro

元代的饒自然著有《繪宗十二忌》,指出山水畫中的十二忌:

1.布置迫塞(章法擁塞,令人透不過氣來)j

2.遠近不分

3.山無氣脈(山石來去的脈絡交代的不清楚)

4.水無源流(水口交待不清,泉水出現得太突然)

5.境無夷險(境界平板缺少變化)

6.路無出入

7.石只一面(畫石缺乏立体感)

8.村少四技(樹枝一般人只畫出左右方向的枝杆,誰于表現向前後伸展的枝杆)

9.人物傴僂(人物畫得彎腰駝背)

10.樓閣錯雜(建築物的布置沒有透視感,且缺乏合理的布局)

11.濃淡失宜(用墨的濃淡不得法,欠協調)

12. 點染無法(包括用墨的點染失調)

雖是說中國山水畫,但應該也和其他繪畫相通。

郎世寧出生於義大利 米蘭 的 聖馬塞蘭諾 (San Marcellino),青年時期在 卡洛科納拉 (Carlo Conara)學習繪畫與建築,並在 1707年 左右加入了 熱那亞 耶穌會 。剛開始只為義大利的 教堂 畫 壁畫 , 1714年 居往在 葡萄牙 里斯本 及 科英布拉 。幾年後對中國產生了相當大的興趣� �曾到 澳門 學習中文﹙他的中文名字就是在澳門� �的﹚,並在 1715年 前往中國。 郎世寧在中國待了相當�� 的時間,從 康熙 、 雍正 、 乾隆 三朝,共計約有50多年,他在1715年到� �國時,被康熙以藝術家的身份召進宮� �,曾協助 圓明園 的規劃設計,他引進西方文藝復興時� �開創的明暗寫實畫法,並改用膠狀顏� �在 宣紙 上作畫,也就是今日的 膠彩畫 作法,他曾試圖要求康熙開辦學習用� �方 透視 原理來繪畫的繪畫學校,但不被採用� �後來與中國學者 年希堯 一起出版了一本《 視學 》,是中國第一部透視學專著。 1757年 ,乾隆曾為郎世寧辦70歲大壽,證明�� 在宮中頗受禮遇及恩寵。他晚年時替�� 隆和其妃子畫了不少的肖像,於 1766年 在中國去世,去世時官至三品,被乾� �追賜封為侍郎銜。享年78歲。葬於 滕公柵欄 。在他之後的西洋傳教士畫家有 王致誠 (Jean Denis Attiret)、 艾啟蒙 (Ignaz Sichelbarth)、 賀清泰 (Louis dePoirot)、 潘廷章 (Giuseppe Panzi) 今日郎世寧的畫作在中國畫拍�� 市場中是相當高價的作品, 2000年 他的《 蘋野秋鳴 》賣出價是1765.5萬 港幣 ,是當時第二高價賣出的中國畫。

milieu

from

Chinese version summary

Back

to Top

Pu Hsin-Yu less perspective

traditional 4:3 to 16:9 high definition (

) more viewing perspective

達文西 繪畫論

第一篇 繪畫與他種藝術之比較

第二篇 畫家守則

第三篇 透視學

第四篇 光影色

第五篇 比例與解剖

第六篇 動態與表情

第七篇 素描與構圖

第八篇 衣服

第九篇 樹木與草地

第十篇 風景與自然現象

第二篇 畫家守則

少年訓練 少年應當先學習什麼

少年應當先學透視 再學習萬物的比例 而後臨摹名家的作品 藉以養成畫好人體各部分的習慣 再繼之以自然作品的臨摹 以鞏固所學的課業 經常觀摩各大師的作品 少年希望精通這門模仿一切自然造物的形狀的科學 應當在學習中注重素描 連同和物體所處置相應的光和影

對學畫兒童應提出什麼法則

在作素描時應當慢慢進行 仔細辨認各種光線中哪些最明亮 陰影之中哪些最黑暗 而明暗又如何交混 觀察他們的份量 並互相比較 注意輪廓的朝向 注意線條上哪段向一邊或另一邊彎曲 哪些地方比較明顯或不明顯 即什麼地方粗什麼地方細 最後 應當留心使你的明暗融合起來 像煙霧一般分不出筆觸和邊界 當你如此用心的熟練了你的手和判斷時 你就會在不知不覺間 已經落筆神速

第三篇 透視學

1. 縮影透視 (線透視) 物體遠離眼睛時看來變小的原因

2. 空氣透視 (色透視) 顏色離眼遠去時變化的方式 物體顏色的淡退

3. 隱沒透視 物體在不同距離處清晰度的減低 物體何以越遠越模糊 (王維 遠人無目 遠樹無枝 遠山無石 遠水無波)(解析度)

Perspective

Drawing 室內透視學

Fundamentals of perspective, shades and shadows; reality and

appearance; and, how we see for perspective drawing.

1.空間對視覺藝術的意義。

What space means to the visual art

2.視覺藝術的空間表現發展歷程。Development progress of space performance of the

visual art

3.透視學理論的認知、熟悉與運用。The cognition, familiarity, and application of the theory of the perspective.\

Translation of: Einstein, Picasso : space, time, and the beauty that causes havoc. (Google Book Search)

There are some viewers, including Chinese, that do not like the idea of Multi-Point Perspective. They insist that it does not reflect reality of distances and sizes as things should be. What is reality? Our eyes may sometimes not tell us the truth - is the car moving on the street faster than the plane in the air? Is Picasso's abstract painting reality?

In the movie "What the Bleep Do We Know?"

The Multi-Point Perspective is a unique Chinese Brush Painting technique and concept that the Chinese believe in the philosophy that the Heaven, Earth, and the Man are all in unison as One. It suggests, but does not impose, the viewers that wherever and whenever we are we are a living part of the the Nature.

Perspective (graphical)

Perspective (from Latin language perspicere, to see clearly) in the graphic arts , such as drawing , is an approximate representation on a flat surface (such as paper ) of an image as it is perceived by the eye. The two most characteristic features of perspective are:

- Objects are drawn smaller as their distance from the observer increases

- Spatial foreshortening, which is the distortion of items when viewed at an angle In art, the term "foreshortening" is often used synonymously with perspective, even though foreshortening can occur in other types of non-perspective drawing representations (such as oblique projection ).

What is Perspective?

Basic concept

Perspective works by representing the light that passes from a scene, through an imaginary rectangle (the painting), to the viewer's eye. It is similar to a viewer looking through a window and painting what is seen directly onto the windowpane. If viewed from the same spot as the windowpane was painted, the painted image would be identical to what was seen through the unpainted window. Each painted object in the scene is a flat, scaled down version of the object on the other side of the window. Because each portion of the painted object lies on the straight line from the viewer's eye to the equivalent portion of the real object it represents, the viewer cannot perceive (sans depth perception ) any difference between the painted scene on the windowpane and the view of the real scene. If the viewer is standing in a different spot, the illusion should be ruined, but unless the viewer chooses an extreme angle, like looking at it from the bottom corner of the window, the perspective normally looks more or less correct. In practice, however, nearly all perspectives (including those created mathematically), introduce distortions in comparison to the view of the real scene. Distortions can occur from:

- mathematical approximations in calculated perspectives

- type of lens used in perspectives generated through photography

- inaccuracies from freehand sketching These distortions are usually introduced knowingly in order to simplify construction of the perspective.

Other related concepts

Some concepts that are commonly associated with perspectives include:

- foreshortening

- horizon line

- vanishing points All perspective drawings assume a viewer, a certain distance away from the drawing. Objects are scaled relative to that viewer. Additionally, an object is often not scaled evenly --- a circle often appears as an ellipse and a square can appear as a trapezoid. This distortion is referred to as foreshortening. Perspective drawings typically have an (often implied) horizon line. This line, directly opposite the viewer's eye, represents objects infinitely far away. They have shrunk, in the distance, to the infinitesimal thickness of a line. It is analogous (and named after) the Earth's horizon . Any perspective representation of a scene that includes parallel lines has one or more vanishing point s in a perspective drawing. A one-point perspective drawing means that the drawing has a single vanishing point, usually (though not necessarily) directly opposite the viewer's eye and usually (though not necessarily) on the horizon line. All lines parallel with the viewer's line of sight recede to the horizon towards this vanishing point. This is the standard "receding railroad tracks" phenomenon. A two-point drawing would have lines parallel to two different angles. Any number of vanishing points are possible in a drawing, one for each set of parallel lines that are at an angle relative to the plane of the drawing. Perspectives consisting of many parallel lines are observed most often when drawing architecture (architecture frequently uses lines parallel to the Cartesian coordinate system ). Because it is rare to have a scene consisting solely of lines parallel to the three Cartesian axes (x, y, and z), it is rare to see perspectives in practice with only one, two, or three vanishing points. Consider that even a simple house frequently has a peaked roof which results in a minimum of five sets of parallel lines, in turn corresponding to up to five vanishing points. In contrast, perspectives of natural scenes often do not have any sets of parallel lines. Such a perspective would thus have no vanishing points.

History of Perspective

Early history

Before perspective, paintings and drawings typically sized objects and characters according to their spiritual or thematic importance, not with distance. Especially in Medieval Art , art was meant to be read as a group of symbols, rather than seen as a coherent picture. The only method to show distance was by overlapping characters. Overlapping alone made poor drawings of architecture; medieval paintings of cities are a hodgepodge of lines in every direction. The optical basis of perspective was defined in the year 1000 , when the Arabia n mathematician and philosopher Alhazen , in his Perspectiva , first explained that light projects conically into the eye. This was, theoretically, enough to translate objects convincingly onto a painting, but Alhalzen was concerned only with optics, not with painting. Conical translations are also mathematically difficult, so a drawing using them would be incredibly time consuming. The artist Giotto di Bondone first attempted drawings in perspective using an algebraic method to determine the placement of distant lines. The problem with using a linear ratio in this manner is that the apparent distance between a series of evenly spaced lines actually falls off with a sine dependence. To determine the ratio for each succeeding line, a recursive ratio must be used. This was not discovered until the 20th Century , in part by Erwin Panofsky . One of Giotto's first uses of his algebraic method of perspective was Jesus Before the Caïf. Although the picture does not conform to the modern, geometrical method of perspective, it does give a decent illusion of depth, and was a large step forward in Western art.

Mathematical basis for perspective

One hundred years later, in the early 1400s , Filippo Brunelleschi demonstrated the geometrical method of perspective, used today by artists, by painting the outlines of various Florentine buildings onto a mirror. When the building's outline was continued, he noticed all the lines all converged on the horizon line. According to Vasari , he then set up a demonstration of his painting of the Battistero di San Giovanni (Florence) in the incomplete doorway of the Santa Maria del Fiore . He had the viewer look through a small hole on the back of the painting, facing the Baptistry. He would then set up a mirror, facing the viewer, which reflected his painting. To the viewer, the painting of the Baptistry and the Baptistry itself were nearly intistinguishable. Soon after, nearly every artist in Florence used geometrical perspective in their paintings, notably Donatello , who started painting elaborate checkerboard floors into the simple manger portrayed in the birth of Christ . Although hardly historically accurate, these checkerboard floors obeyed the primary laws of geometrical perspective: all lines converged to a vanishing point, and the rate at which the horizontal lines receded into the distance was graphically determined. This became an integral part of Quattrocento art. Not only was perspective a way of showing depth, it was also a new method of Composition (visual arts) a painting. Paintings began to show a single, unified scene, rather than a combination of several. As shown by the quick proliferation of accurate perspective paintings in Florence, Brunelleschi likely understood, but did not publish, the mathematics behind perspective. Decades later, his friend Leon Battista Alberti wrote Della Pittura , a treatise on proper methods of showing distance in painting. Alberti's primary breakthrough was not to show the mathematics in terms of conical projections, as it actually appears to the eye. Instead, he formulated the theory based on planar projections, or how the rays of light, passing from the viewer's eye to the landscape, would strike the picture plane (the painting). He was then able to calculate the apparent height of a distant object using two similar triangles. In viewing a wall, for instance, the first triangle has a vertex at the user's eye, and vertices at the top and bottom of the wall. The bottom of this triangle is the distance from the viewer to the wall. The second, similar triangle, has a point at the viewer's eye, and has a length equal to the viewer's eye from the painting. The height of the second triangle can then be determined through a simple ratio, as proven by Euclid . Piero della Francesca elaborated on Della Pittura in his De Prospectiva Pingendi in 1474 . Alberti had limited himself to figures on the ground plane and giving an overall basis for perspective. Francesca fleshed it out, explicitely covering solids in any area of the picture plane. Francesca also started the now common practice of using illustrated figures to explain the mathematical concepts, making his treatise easier to understand than Alberti's. Francesca was also the first to accurately draw the Platonic solids as they would appear in perspective. Perspective remained, for a while, the domain of Florence. Jan van Eyck , among others, was unable to create a consistent structure for the converging lines in paintings, as in London's The Arnolfini Portrait , because he was unaware of the theoretical breakthrough just then occurring in Italy. at the Sistine Chapel ( 1481 1482 ) helped bring the Renaissance to Rome .

Artificial and natural

Leonardo da Vinci distrusted Brunelleschi's formulation of perspective because it failed to take into account the appearance of objects held very close to the eye. Leonardo called Brunelleschi's method artificial perspective projection. It is today called classical perspective projection. Projections closer to the image beheld by the human eye , he named natural perspective. Artificial perspective projection is a perspective projection onto a flat surface, well suited for drawings and paintings, which are typically flat. Natural perspective projection, in contrast, is a perspective projection onto a spherical surface. From a geometric point of view, the differences between artificial and natural perspectives can be thought of as similar to the distortion that occurs when representing the earth (approximately spherical) as a map (typically flat). Both types of projection involve a distortion. The difference between the two distortions is called perspective projection distortion .

Varieties of Perspective Drawings

Of the many types of perspective drawings, the most common categorizations of artificial perspective are one-, two- and three-point. The names of these categories refer to the number of vanishing point s in the perspective drawing. Strictly speaking, these types can only exist for scenes being represented that are rectilinear (composed entirely of straight lines which intersect only at 90 degrees to each other).

One-point perspective

One vanishing point is typically used for roads, railroad tracks, or buildings viewed so that the front is directly facing the viewer. Any objects that are made up of lines either directly parallel with the viewer's line of sight (like railroad tracks) or directly perpendicular (the railroad slats) can be represented with one-point perspective. One-point perspective exists when the painting plate (also known as the picture plane ) is parallel to two axes of a rectilinear (or Cartesian) scene --- a scene which is composed entirely of linear elements that intersect only at right angles. If one axis is parallel with the picture plane, then all elements are either parallel to the painting plate (either horizontally or vertically) or perpendicular to it. All elements that are parallel to the painting plate are drawn as parallel lines. All elements that are perpendicular to the painting plate converge at a single point (a vanishing point) on the horizon.

Two-point perspective

Two-point perspective can be used to draw the same objects as one-point perspective, rotated: looking at the corner of a house, or looking at two forked roads shrink into the distance, for example. One point represents one set of parallel lines, the other point represents the other. Looking at a house from the corner, one wall would recede towards one vanishing point, the other wall would recede towards the opposide vanishing point. Two-point perspective exists when the painting plate is parallel to a Cartesian scene in one axis (usually the z-axis) but not to the other two axes. If the scene being viewed consists solely of a cylinder sitting on a horizontal plane, no difference exists in the image of the cylinder between a one-point and two-point perspective.

Three-point perspective

Three-point perspective is usually used for buildings seen from above. In addition to the two vanishing points from before, one for each wall, there is now one for how those walls recede into the ground. Looking up at a tall building is another common example of the third vanishing point. Three-point perspective exists when the perspective is a view of a Cartesian scene where the picture plane is not parallel to any of the scene's three axes. Each of the three vanishing points corresponds with one of the three axes of the scene.

Zero-point perspective

Due to the fact that vanishing points exist only when parallel lines are present in the scene, a perspective without any vanishing points ("zero-point" perspective) occurs if the viewer is observing a nonlinear scene. The most common example of a nonlinear scene is a natural scene (ie, a mountain range) which frequently does not contain any parallel lines. Other examples include: a random (ie, not aligned in a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system) arrangement of spherical objects, a scene composed entirely of three-dimensionally curvilinear strings, or a scene consisting of lines where no two are parallel to each other. Orthographic projection also do not have vanishing points, but they are not perspective constructions and are thus not equivalent to a "zero-point" perspective. Note that a perspective without vanishing points can still create a sense of "depth," as is clearly apparent in a photograph of a mountain range (for example, more distant mountains have smaller scale features).

Other varieties of linear perspective

One-point, two-point, and three-point perspective are dependent on the structure of the scene being viewed. These only exist for strict Cartesian (rectilinear) scenes. By inserting into a Cartesian scene a set of parallel lines that are not parallel to any of the three axes of the scene, a new distinct vanishing point is created. Therefore, it is possible to have an infinite-point perspective if the scene being viewed is not a Cartesian scene but instead consists of infinite pairs of parallel lines, where each pair is not parallel to any other pair.

Varieties of nonlinear perspective

Typically, mathematically constructed perspectives are "linear" in that the ratio at which more distant objects decrease in size is constant (ie, graphing the drawn size of a one-foot object versus the distant from viewer will form a straight line). It is conceivable to have non-linear perspectives those in which the graph of the ratio mentioned above does not form a straight line. A panorama is a perspective projected onto a cylinder. The actual drawing can be drawn onto a cylinder (typically on the interior surface and viewed from the inside the cylinder) or onto a flat surface, equivalent to "unrolling" the cylinder. A panorama (projection onto a cylinder) removes one of the differences between artificial perspective projection (projection onto a flat surface) and natural perspective projection (projection onto a spherical surface). A standard Mercator projection is similar to a panorama.

Methods of Constructing Perspectives

Several methods of constructing perspectives exist, including:

- Freehand sketching (common in art)

- Graphically constructing (once common in architecture)

- Using a perspective grid

- Computing a perspective transform (common in 3D computer applications)

- Mimicry using tools such as a proportional divider (sometimes called a variscaler )

Example: a checkerboard in perspective

One of the most common, and earliest, uses of geometrical perpective is a square tiling . It is a simple but striking application of one-point perspective. The artist starts by drawing a horizon line and determining where the vanishing point should be. The higher up the horizon line, the lower the viewer will appear to be looking, and vice versa. The more off-center the vanishing point, the more tilted the checkerboard will be. Because the checkerboard is made up of right angles, the vanishing point should be directly in the middle of the horizon line. A rotated checkerboard is drawn using two-point perspective. The foremost edge of the checkerboard is drawn near the bottom of the painting. Lines connecting each edge of the checkerboard to the vanishing point give the left and right sides. The bottom line of the checkerboard is then divided evenly. Because each checker is a square, this gives both the width of each column of checkers and will be used to determine the height of each row. Each division is connected from the bottom of the checkerboard to the vanishing point. A new point is now chosen, on the horizon line, either to the left or right of the vanishing point. This distance from this point to the vanishing point represents the distance of the viewer from the drawing. If this point is very far from the vanishing point, the checkerboard will appear squashed, and far away. If it is close, it will appear stretched out, as if it is very close to the viewer. Lines connecting this point to each division on the bottom of the checkerboard are drawn. Where each line connects with the side of the checkerboard, a new row of checkers is marked. Original formulations used, instead of the side of the checkerboard, a vertical line to one side, representing the picture plane. Each line drawn through this plane was identical to the line of sight from the viewer's eye to the drawing, only rotated around the y-axis ninety degrees. It can be easily shown that both methods are mathematically identical, and result in the same vertical spacing of checkers. This step is key to understanding perspective drawing. The light that passes through the picture plane obviously can not be traced. Instead, lines that represent those rays of light are drawn on the picture plane. Once all extraneous lines are erased, the checkers are filled in.

Foreshortening

Foreshortening refers to the visual effect or optical illusion that an object or distance is shorter than it actually is because it is angle d toward the viewer. Although foreshortening is an important element in art where visual perspective (graphical) is being depicted, foreshortening occurs in other types of two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional scenes. Some other types where foreshortening can occur include oblique projection drawings. Figure F1 shows two different projections of a stack of two cubes, illustrating oblique parallel projection foreshortening ("A") and perspective foreshortening ("B").

Limitations of Perspective

Producing a perspective drawing on a flat surface, whether sketched or calculated, is always an approximation. It necessarily incurs some distortion from what would be perceived by the eye due to the nature of the geometry transforms involved. A perspective drawing, whether roughly sketched (ie, intuitively by freehand) or precisely calculated (i.e., using matrix multiplication on a computer or other means), is usually a combination of two geometry transforms:

- A perspective transform : a perspective projection onto a typically flat picture plane (or painting plate) of a scene from the viewpoint of an observer

- A similarity transform: a scaling of the picture plane from the first transform onto an actual drawing of a usually smaller size. An exact replication of the image perceived by the eye is only possible when the picture plane is a spherical surface or portion of a spherical surface (with the center of the sphere located at the observer's eye). The distortion that occurs is similar to the distortions that occur when attempting to represent the globe (approximately spherical) on a flat surface (see perspective projection distortion ).

在一般人的印象中,認為只有西洋畫有透視,傳統的中國畫沒有透視。這是不符合事實的。傳統的中國畫的透視方法與西洋畫的透視方法有很大的不同,西洋畫講究焦點透視法,傳統的中國畫講究散點透視法。所謂焦點透視法,就是嚴守一個特定的視點去表現景物,近大遠小,呈放射狀。散點透視法不拘泥于一個觀點,它是多視點的,在表現景物時,它可以將焦點透視表現的近大遠小的景物,用多視點處理成平列的同等大小的景物。散點透視法,可以比較充分地表現空間跨度比較大的景物的方方面面,這是傳統中國畫的一個很大的獨特優點。

例如宋代張擇端的《清明上河圖》長卷,它用散點透視的多視點原理,把古代汴京東郊以虹橋為中心的風景、人物、城郭、街道、橋梁。船只等等豐富內容的場面散點在一個畫面,給予了充分詳盡的表現。如果用西洋畫的焦點透視法,它只能突出地表現畫家確定的一個視點周圍的景物,也只能將其它許多景物根據近大遠小的原則虛隱掉。

傳統的中國畫並非不重焦點透視,它不過是在一幅畫中根據需要採用多個焦點透視而已。這是傳統中國畫區別于西洋畫的一個重要特點。中國古代或許沒有系統的透視學,但對于科學的焦點透視法,也早有樸素的深刻認識。早于德國透視畫家丟勒一千多年的六朝劉宋時期的宗炳,就曾寫過一篇《畫山水敘》說明了透視學中按比例遠近布置物景的法則。但中國畫家多喜歡表現空間跨度大的山川江河,甚至想把整條長江都畫到一幅畫中,他們不滿足于用一個焦點來束縛自己的視野,因此,中國畫家多採用移動式、減距式、以大觀小的散點透視法來表現無限豐富的景象。這種手法給畫家帶來了空間處理上的自由。

相對西洋畫來說,中國畫有著自己明顯的特征。傳統的中國畫不講焦點透視,不強調自然界對于物體的光色變化,不拘泥于物體外表的肖似,而多強調抒發作者的主觀情趣。中國畫講求以形寫神,追求妙在似與不似之間的感覺

而西洋畫則講求以形寫形,當然,創作的過程中,也注重神的表現。但它非常講究畫面的整體、概括。有人說,西洋畫是再現的藝術,中國畫是表現的藝術。

中國畫與西洋畫相比有著自己獨特的特征,還表現在其藝術手法、藝術分科、構圖、用筆、用墨、敷色等多方面。按照藝術的手法來分,中國畫可分為工筆、寫意和兼工帶寫種三形式。工筆就是用畫筆工整細致,敷色層層渲染,細節明徹入微,用極其細膩的筆觸描繪物象,故稱工筆。而寫意相對工筆而言,用豪放簡練的筆墨描繪物象的形神,抒發作者的感情。它要有高度的概括能力,要有以少勝多的含蓄意境,落筆要準確且抒放,運筆要熟練能得心應手,意到筆到。兼工帶寫的形式則是把工筆和寫意兩種方法進行綜合的運用。

國畫在構圖、用筆、用墨、敷色等方面有自己的特點。國畫的構圖一般不遵循西洋畫的黃金律,而是或作長卷,或作立軸,長寬比例是失調的。但它能夠很好表現特殊的意境和畫者的主觀情趣。

同時,在透視的方法上,中國畫與西洋畫也是不一樣的。透視是繪畫的術語,就是在作畫的時候,把一切物體正确地在平面上表現出來,使之有遠近高低的空間感和立體感,這種方法就叫透視。因透視的現象是近大遠小,所以也常常稱作遠近法。

西洋畫一般是用焦點透視,這就像照相一樣,固定在一個立腳點,受到空間的局限,攝入鏡頭的就如實照下來,否則就照不下來。中國畫就不一定固定在一個立腳點作畫,也不受固定視域的局限,它可以根據畫者的感受和需要,使立腳點移動作畫,把見得到的和見不到的景物統統攝入自己的畫面。國畫的透視的方法,叫做散點透視或多點透視。如我們所熟知的北宋名畫、張擇端的《清明上河圖》,用的就是散點透視法。《清明上河圖》反映的是北宋都城汴梁內外氣象萬千的景象。它以汴河為中心,從遠處的郊野畫到熱鬧的虹橋;觀者既能看到城內,又可看到郊野;既看得到橋上的行人,又看得到橋下的船;既看得到近處的樓台樹木,又看得到遠處縱深的街道與河港。而且無論站在哪一段看,景物的比例都是相近的,如果按照西洋畫焦點透視的方法去畫,許多地方是根本無法畫出來的。這是中國的古代畫家們根據內容和藝術表現的需要而創造出來的獨特的透視方法。

在用筆和用墨方面,是中國畫造型的重要部分。用筆講求粗細、疾徐、頓挫、轉折、方圓等變化,以表現物體的質感。一般來說,起筆和止筆都要用力,力腕宜挺,中間氣不可斷,住筆不可輕挑。用筆時力輕則浮,力重則飩,疾運則滑,徐運則滯,偏用則薄,正用則板。要做到曲行如弓,直行如尺,這都是用筆之意。古人總結有勾線十八描,可以說是中國畫用筆的經驗總結。而對于用墨,則講求皴、擦、點、染交互為用,干、濕、濃、淡合理調配,以塑造型體,烘染氣氛。一般說來,中國畫的用墨之妙,在于濃淡相生,全濃全淡都沒有精神,必須有濃有淡,濃處須精彩而不滯,淡處須靈秀而不晦。用墨亦如用色,古有墨分五彩之經驗,亦有惜墨如金的畫風。用墨還要有濃談相生相融,做到濃中有淡,淡中有濃;濃要有最濃與次濃,淡要有稍談與更淡,這都是中國畫的靈活用筆之法。由于中國畫與書法在工具及運筆方面有許多共同之處,二者結下了不解之緣,古人早有書畫同源之說。但是二者也存在顯著差異,書法運筆變化多端,尤其是草書,要勝過繪畫,而繪畫的用墨豐富多彩,又超過書法。筆墨二字被當做中國畫技法的總稱,它不僅僅是塑造形象的手段,本身還具有獨立的審美價值。

中國畫在敷色方面也有自己的講究,所用顏料多為天然礦物質或動物外殼的粉末,耐風吹日晒,經久不變。敷色方法多為平塗,追求物體固有色的效果,較少光影的變化。

以上談的中國畫的特點,主要是指傳統的中國畫而言。但這些特點,隨著時代的前進,藝術內容和形式也隨之更新 。特別是五四運動之后,西洋畫大量涌入,中國畫以自己寬闊的胸懷,吸收了不少西方藝術的技巧,豐富了中國畫的表現力。但是,不管變化如何,中國畫傳統的民族的基本特征不能丟掉,中國畫的優良傳統應該保持並發揚光大,因為中國畫在世界美術領域中自成獨特的體系,它在世界美術万花齊放,千壑爭流的藝術花園中獨放异彩。中國畫是我們民族高度智慧、卓越才能和辛勤勞動的結晶,是我們民族的寶貴財富。 >>> 2nd copy to Intro

透視,是繪畫術語。畫家在作畫的時候,把客觀物象在平面上正确地表現出來,使它們具有立体感和遠近空間感,這种方法叫透視法。因為透視現象是近大遠小的,所以也稱為遠近法。西洋畫一般是采用焦點透視,它就象照相一樣,觀察者固定在一個立足點上,把能攝入鏡頭的物象如實地照下來,因為受空間的限制,視域以外的東西就不能攝入了。中國畫的透視法就不同了,畫家觀察點不是固定在一個地方,也不受下定視域的限制,而是根据需要,移動著立足點進行觀察,凡各個不同立足點上所看到的東西。都可組織進自己的畫面上來。這种透視方法,叫做散點透視,也叫移動視點。中國山水畫能夠表現颶尺千里的遼闊境界,正是運用這种獨特的透視法的結果。

中國山水畫透視法的形成,有著悠久的歷史。早在南北朝時代,宗炳的《畫山水序》中就說:去之稍闊,則其見彌小。今張絹素以遠映,則昆閬(昆侖山)之形,可圍千方寸之內;豎畫三寸,當千切之高;橫墨數尺,体百里之迥。他說的是用一塊透明的絹素,把遼闊的景物移置其中,可發現近大遠小的現象。這是在繪畫史上對透視原理的最早論述。到了唐代,王維所撰《山水論》中,提出處理山水畫中透視關系的要訣是:丈山尺樹,寸馬分人,遠人無目,遠樹無枝,遠山無石,隱隱,眉(黛色),遠水無波,高与云齊。可見當時山水畫家都是重視透視規律的。到了宋代,中國山水畫透視法已形成

了完整的体系。

所謂散點透視是中國人因為外國人說我們畫畫沒有透視不服气硬加上去的名詞,其實早期傳統的中國畫就是沒有嚴格的透視,沒有統一的消失點,近窄遠寬的事也時有發生,雖然也注意到了一些透視變化規律但是沒有像西洋人那樣加以系統的精确的研究和理論化。只有到了洋人把油畫帶入中國,中國的繪畫才開始有真正嚴謹的透視。

可是這有什么不好么?!何必不服气呢?中國畫有中國畫的藝術追求,沒必要把西洋繪畫的尺度強加于自己

My pottery painting