A9: How to Self Criticize

“Always

be your own severest critic. Be not easily satisfied with yourself. Hitch your

wagon to a star. Let your standard of perfection be the very highest. Always

strive to reach that standard. Once secured, it’s the greatest asset an artist

can possess.”

Rigorous

self-criticism is indispensable for an artist to look for his or her weakness and

strength. Any tolerance or self-consolation is a hindrance to the artist’s

maturity. A good Chinese calligrapher should stay away from all charlatanism

both technically and mentally. The

following is a step-by-step illustration of self-criticizing a Chinese character

and how to make it better in a number of proposed ways.

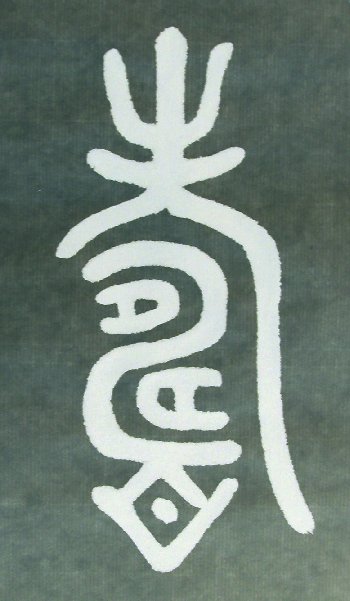

At

first glance, this character “longevity” may look neat and organized to an

amateur. What is the deficiency of this character? If we still cannot find it,

an easy way is to make a “negative image.” Then, we may treat the white portion as “chunky strokes” and the

black portion as “black space.”

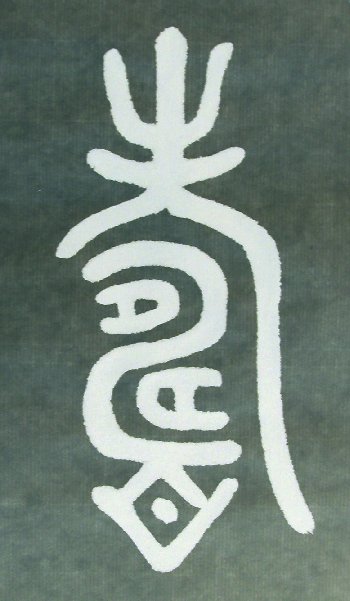

Then let me make a series of self confessions by criticizing it “from head to toe.”

The

two strokes in the head (1) need to be adjusted. The one on the

right has some deficiency and I add it up. The head in the middle may not have

tilted neck here. So I adjust leftward a little bit.

Then

I move up the “orange color” portion a little bit upward in order to let the “gate”

(2) open for more energy flow. Or else it’s choked.

As

the energy flows in, it comes to a bottleneck near (3). So I move the stroke a

little bit downward to continue the flow through.

Then

I find the energy flow might not be appropriate at (4). So I suggest the

position to be at the dotted line.

Then

I find the stroke at (5) a little fatty. I make it to lose some weight or else it looks

collapsed around that corner.

Then I make it consistent by “rounding” (6) and (7).

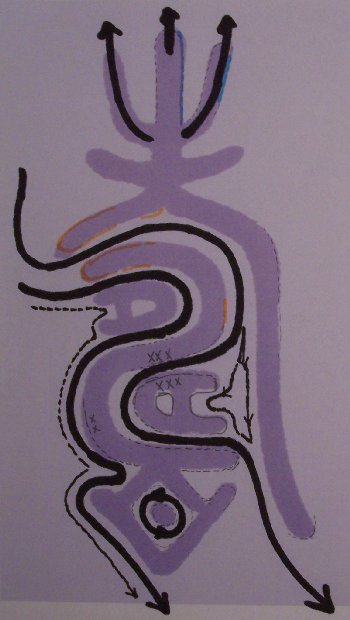

Finally,

I present a “proposed” new look for this character. The thick and dark lines

denote the major energy flows while the dotted lines denote the sub cycles of energy

flow. You may think of this as “the aura of a Chinese character.”

As Deng Shu-Ru referred “Horses

cannot pass through the loose area while wind cannot blow through the tight

area.”

It’s all about “balance”, “harmony”, and “the Tao of the Middle

Way.”

However,

these are just rough proposals. If we repeat the above steps over and over again

and keep asking ourselves honesty without any self-pity, we will find that even

many Chinese calligraphy masters in later dynasties showed such

“deficiencies” and “inappropriateness” in more places than the earlier

calligraphers did. Only after we repeat criticizing ourselves and other

calligraphers will we eventually approach to a higher maturity as exemplified in the

earliest Chinese calligraphy works.

A

Chinese old man used to say, “I

have walked on bridges longer than you walk on the roads; and I have had more

salt than you eat rice.”

A master Chinese calligrapher might say the same thing: “I

have torn more paper than you have written on.”

They are simply referring to “experience” rather than bragging. Don’t

frustrate to start it over again and again. Just try it!

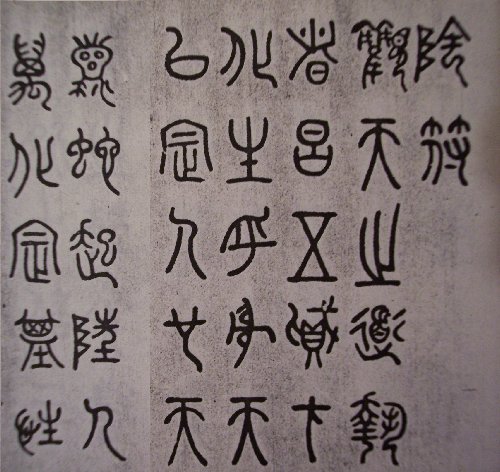

Criticizing

is a factor of progress and success. This can be applied to others besides to

one self. Throughout the Chinese calligraphy history, only very few masters

could survive criticism in each dynasty. Even a great master like Deng Shu-Ru (

鄧

石

如

)

might have done the following so-so work for social or catering purposes. If we

cut some examples from Jin Wen ( 金

文

)

inscriptions and paste by each character at its side, we may find the depth of

the ancient masters is way, way higher than later followers. That’s why

lifetime Lin Mo is absolutely indispensable.

.jpg)