A10: Common Notions

There

are many popular notions or misconceptions about Chinese calligraphy known to the general public. Even

most learned Chinese are preoccupied with some assumptions or misconceptions

about Chinese calligraphy whether the notions can be correct, incorrect,

appropriate, or inappropriate. Art is all about perceptions, feelings, and

esthetics; they are not textbook standards or statements, or associated with

one's educational degrees, social status, and political affiliations. After we have studied the works, theories, and

principles of ancient Chinese calligraphy masters, we may find the following

common notions or misconceptions widely held by most people.

| Size of Calligraphy | Write Neatly | Fast Writing |

| Content of Calligraphy | Clear Models | Life of A Brush |

| Seals & Signatures | Erasure | To Be Added |

Most

people think the larger the Chinese character’s size is, the better and more expensive

the work is.

Character

sizes around 3 x 3 inches are the easiest and most common. Characters as large

as 9 x 9 inches demand a higher level of skill and physical strength. Characters

smaller than 0.5 x 0.5 inches demand the highest level of precision in regard to

skills,

physical strength, and optimal personal well being. That's why Chinese

calligraphers specializing in Small Characters are very rare throughout each

dynasty. Just as

technique is the fundamental of art, precision is the soul of techniques.

A work of Small Characters demands the highest level of skill.

Many Chinese calligraphy practitioners often try to impress the average audience with super large writings. However, as long as delicacy, spirit, and strong will are embodied in each strokes, the size of writing is not a decisive factor to rate the work.

Some

people prefer writing to be neatly arranged, not scattered.

Ancient Chinese calligraphers did not write neatly inside grids. They did the art with a natural and peaceful mind. The work was not to be confined or measured. It is said that a student of Zhong Yao tried to write neatly in one size, then he was so scorned by his teacher that he dared not see him for three years.

It was until the time

(approximately the Tang Dynasty) when people began to use Chinese calligraphy as a means to gain positions of government

officers and be recognized by the judges in the civil service examinations that they began to write neatly or

inside grids. Some of those styles are called Guan

Ge Te ( 館閣體 ,

the monotonous court style of calligraphy

).

The

term 館閣體

refers to a "trend"

or a "temperament" of writing neatly and monotonously without spirit rather than

a major style or a sub

style of

Chinese calligraphy. 館閣體

look neat but lack spiritual and philosophical depth. They have never been seriously regarded by Chinese

calligraphers or scholars. Every character in "Guan

Ge Te" looks like

the same without obvious variations in size, expression, strokes, and writing speed.

The invention of 館閣體

was one of the starting points when Chinese calligraphy began to

fade in artistic levels! Today

if we don’t write neatly, we may not get a reward in most contests. People

eventually forget the original state of Nature and mind. There are no identical

leaves, trees, and mountains in Nature. And we just begin to separate ourselves

away from Nature!

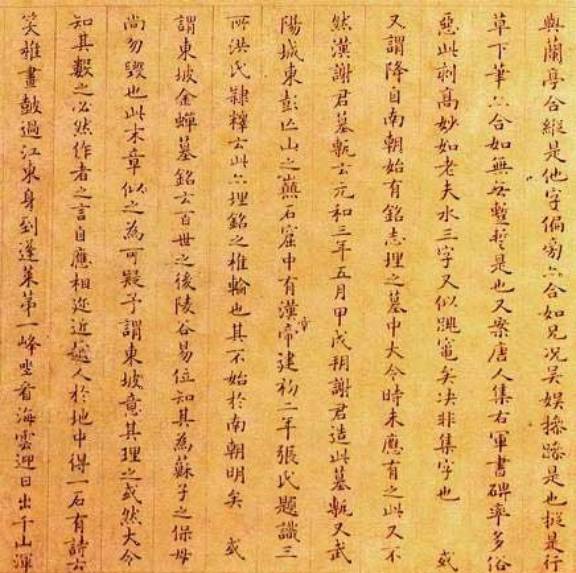

The first and second works possess enormous beauty and more spirit while the third one looks more man-made and confined.

Modern

Chinese calligraphy contests usually require the contestants finish their works

in a limited time span. Most audiences will be astonished by a “fast”

calligrapher with a fluent and stunning speed in a public demonstration.

Our

eyes may deceive us. When we watch an airplane and a car moving, can our eyes

tell us which is moving faster? Time is relative, not absolute. It depends on

the observer’s position.

Not

only Chinese calligraphy adopts the importance of “slow practice” which is

quite contrary to the public notion. Carl Tausig, Franz Liszt’s favorite and number one student, would play every piece,

every note and detail very, very slowly again on the piano right after each

concert. He was such a brilliant pianist that his master and colleagues gave him

the highest compliments. It was said that until his death Tausig had no equal.

The Chinese internal martial artists also have a saying, “Slow

is fast!”

Every

masterpiece of the “Bei School 碑學”

stone rubbings shows us that the ancient calligrapher had gone through a lengthy

process of meditation and mental design. When they were commissioned to do a

great work for the emperors, scholars, or important events, they would go home

practicing again and again, contemplate for months, design and improve mentally

over and over until they reached their best level that are mostly unsurpassed by

later calligraphers in that particular style.

A

work produced after weeks or months of preparation looks more stable and rich in

spirit.

A

work done in a shorter time possessed less depth in spirit and essence.

This is why I do not have a fully commercialized website to sell my works promptly with features that the customers can choose "any" desired phrase, length, width, style, and fast delivery to fit in today’s Internet business. By doing this catering, I believe it’s against the legacy and spirit of Chinese calligraphy. I deeply appreciate those with their respect, understanding, and patience from the bottom of my heart.

The topic of speed in doing Chinese calligraphy is somewhat metaphysical, especially considering the mental design, Gee & Se, and many other physical, technical, and spiritual factors. It might not be understood from the speed or velocity as in physics or sciences. Science can never measure the "speed" and "quantity" of a mother's love. According to some Chinese calligraphers in our time, we agree the writing speed of the calligraphers in the Jin and Tang Dynasties (the golden eras of Chinese calligraphy) were moderate, not hurrying. It means that their speed was neither fast nor slow, could be either fast and slow, or anything in between, transcendental, or metaphysical. A mere bragging of one's ability to write certain number of Chinese characters per minute or per hour is evidently showing one's lack of real knowledge and skills of Chinese brush arts, where these may happen often among amateurs, beginners, and pedants who have read many Chinese calligraphy books from libraries.

People

want their desired content more than the artistic level in a Chinese calligraphy

work.

Most

Chinese and non-Chinese both prefer to choose something more meaningful to them

rather than the level of the art itself. It’s not right to ask people to

change their attitude of what they are looking for. What we can do here is to

enhance the public consciousness and knowledge of what a traditional and

authentic Chinese calligraphy work appears to be in terms of its artistic level.

Chinese calligraphy uses Chinese characters as its only medium of expression. Unless you also practice Chinese calligraphy, a viewer does not have to know Chinese to appreciate its beauty because Chinese calligraphy is an abstract art. When viewing Chinese calligraphy, one need not ask, "What do those Chinese writing mean?", "What is this style?" or even "Who did this?" In viewing a beautiful work, one does not necessarily ask or worry about "What is it?" Just relax and look at them for enjoyment and let the Art of Chinese Calligraphy sooth our mind, except that you are studying this art very seriously.

Most

Chinese poems and calligraphy masterpieces were articles that are not at all

related to our modern life. They

were written in Classical Chinese Style (Wen Yen Wen

文言文

)

and need to be deciphered or translated into Plain Conversation Style (Bai Hua Wen 白話文

).

Some of the calligraphy masterpieces were ancient and rare poems and they presented to us

the depth of beauty within. Most of the famous poets in ancient China were not

necessarily great calligraphers while most calligraphers’ poems were not very

well known compared to those of famous poets. However, the calligraphers wrote

their articles or letters according to the “genre” that best fitted into the realms of

Chinese calligraphy in terms of the selection and sequence of Chinese

characters. The ancient Chinese calligraphers and scholars did favor some

characters and used them frequently. They might have disliked some characters

and they rarely or never used in their writing or calligraphy. For example, in

ancient China, people wrote in classical Chinese. The English words

“you” or “thou” can be translated into “ 汝

”,

“ 爾

“ or ” 你.”

The ancient Chinese rarely wrote ” 你.”

And ancient calligraphers almost never wrote ”你“.

Instead, in classical Chinese it was usually written as “ 汝

”

and “ 爾

“ while ancient calligraphers mostly

favored “ 汝.”

Even though those three characters mean the same “you,” calligraphers

preferred “ 汝”

to ” 你

” for artistic reasons. If you have learned

Tsao Style, you will understand why.

Just

like a composer likes to use certain methods in counterpoint or harmony to

create a musical phrase, there are some methods or forms that some composers do

not like to use. A Beethoven piano sonata was to be played on the piano,

not meant to be played on the violin or by the symphony by the composer though

people have freedom for rearragenment. To some degree, Chinese calligraphy will

best fit in the genre of ancient Chinese articles or poems rather than any words

from commercial or political campaign in terms of artistic level and depth.

Most

beginners want to choose clearer, amended, "restored," or enhanced versions of

stone rubbings ( 拓本 ) instead of the earlier and original

ones that are faithfully rubbed, duplicated, and printed.

Most

beginners do not have an idea of what the original rubbings of ancient

characters look like. Some rubbings are so vague that is beyond reading.

Publishers thus amend or make up (they prefer to call "restore") clearer versions of rubbings to cater the

beginner’s mind and preference for convenience.

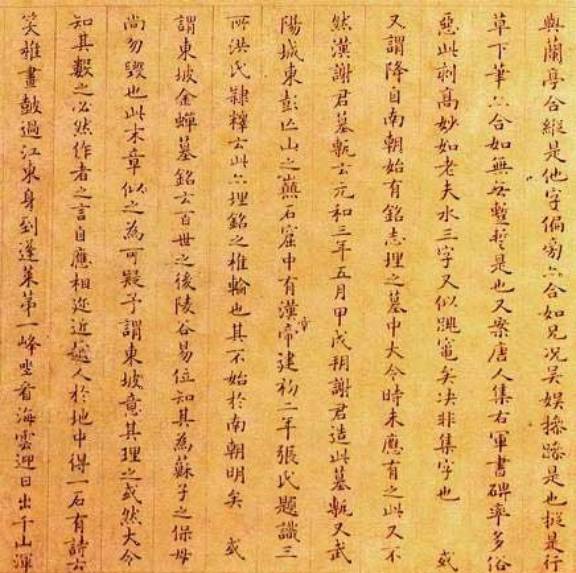

If

we look closely and examine the details in the bottom row of the above samples,

we will find nuances and details being changed by the publisher. The publishers

are not necessarily calligraphers. Even if they are, any amending in any kind,

no matter how small or nuanced, will destroy or distort the original spirit and probably the

positions, strokes, and thickness to some extent since Chinese and calligraphy

theorists consider Chinese calligraphy as "heart print" of "the

track of heart." Those "restored"

versions are merely camouflage. Even if you are just a

beginner or a non-Chinese, be sure to choose the original and earlier version

over the “clearer and amended” version. It’s permissible to buy both

“original” and “amended” versions for comparison. But only the

“original” version can be used for Lin Mo practice.

However,

if you are not a Chinese and just start learning Chinese language and/or

calligraphy, it’s okay for you to use this kind of “amended” or

“clearer” rubbings. As you have made more progress, it’s advisable that

you stay away from those versions and get the real and faithful ones.

Most

people assert that a brush will last for an average of few years, probably one

or two if you practice diligently. When I started

learning Chinese calligraphy, I practiced diligently with only one brush for one

style. I did not know how to take care of it by washing it properly. And of

course, I did not know any theories or principles of operating a brush. All I

knew were some basic rules my teacher taught me. So I ended up changing a brush

every year.

As

I grew up, I eventually began to have a better habit of writing. So it seemed

that my brushes lasted longer than when I was in grade school. And then in high

school when I became more devoted, I used only one "all-around" brush (Jian Hao 兼毫,

a combination brush)

to practice all styles I knew.

Then

as I read and knew more and more about the theories, operating principles, and styles, my

brushes I bought since 1990 are still in excellent conditions. None of them are short-lived again! (I do prefer some of them

and dislike some of them.) Since I know the proper operation and maintenance of

brushes, I no longer worry that they will wear out soon. I do believe they will

last lifetime or at least decades. Even though some of them are wearing out at

the tip a little bit due to frequent practice, I can still use those as featured

brushes to write other styles with a desirable effect or explore and experiment

different possibilities such as the textures in brush painting.

Unless a brush is made low grade, I will say a brush should last lifetime if we know how to respect it and apply the Center Tip Principle ( 中鋒 ). I suggest washing every time right after every practice – gently and respectfully.

Some people think that a Chinese calligraphy or painting work

should be signed and stamped with seals, at least to prevent future holders to

sign it.

The writing of a Chinese calligraphy work is the "main

content" of the work itself. The signatures and seals personalize the work.

Mounting ( 裝裱 ) is for display and preservation purposes. According to the

perspectives of Chinese culture such as 主次分明, we may think

of the main calligraphy content as the host, the signature and seals as the

guests, and the frame or the mounted scroll as a hall or a house. A perfect

party will consist a noble host, decent guests, and a majestic hall. A good

Chinese calligraphy work will be more valuable if it can meet the above three

conditions.

However, the main content is the most important and the signature

and seals are the most critical. We may consider having an outdoor party with

good programs, the host, and visitors without staying in a building. But if we

invite vulgar guests to the party, the main event will be totally ruined. It's

recommended that a good Chinese calligraphy work be framed or mounted according

to the Chinese notion of 佛要金裝,人要衣裝. If the frame

or the mounted scroll is poor or vulgar, it will totally devalue the entire work

no matter how great the calligraphy and seals are. If the mounting and (or) the

seals exceed the main content in artistic levels, they will add more value to

the calligraphy. However, if either the mounting or the seals are not good

enough to match the calligraphy's level, that work will absolutely be demeaned. This

is why famous calligrapainting masters always have a good business relationship

with professional and reliable mounters ( 裝裱師傅 ) and seal

carvers, or they have learned to mount calligrapainting and carve seals

themselves.

Similarly, if a Chinese painting work contains a poem written in

nice calligraphy and is stamped with nice seals, it's the perfect combination of

Chinese calligraphy, painting, seals, and literature. (That's one of the reasons

why Chinese calligraphy, painting, and seal making are sister arts.) But if any

one of the three add-ons (calligraphy, seal, or poem) is below the painter's

level a lot, it will ruin the whole work no matter how great the painting is!

In early dynasties like Han, calligraphers did not care so much

about personalizing their works. In fact, many of the best ancient masterpieces

remained anonymous. The original artists realized the cosmic harmony existed in

the nature and many things were not created or personally owned by the artists

individually. They cared for the level of art more than personal

recognition. This great philosophy is different from modern and Western way of

signing and personalizing an artwork. I was once asked by people who do not know

Chinese culture, philosophy, and calligraphy about leaving a Chinese painting or

calligraphy work unsigned or anonymous. They doubt that if a Chinese painter or

calligrapher does not sign his / her work, later it may be possessed by someone

who signs it and sell for higher prices! (What a joke and honor! Once when a

famous Chinese painter found out there were more forgeries of his work in

the market than his real work he painted himself, he said, "it's plausible

to create fake imitations or duplicates of a deceased master, but I am still

alive!" ) That "someone" must possess at least the same artistic

(calligraphic) and moral levels of the original artist in order to sign a

painting or calligraphy work without totally destroying its value.

"Someone" who has reached a high level, of course, need not sign

other's works - they can create their own good works! So if a Chinese painting

or calligraphy work is good and anonymous, the original artist may have realized

the ancient philosophy of "Not Possessing" even though it may not be

compatible with today's business concepts.

|

The following articles are not written

by Joshua; I did not make those rules. Nor does anyone have authority to

dictate those rules or norms to everyone who does Chinese calligraphy

and painting. IMHO and according to my other art friends' opinions,

these "summarized" norms and/or rules are meant to be observed

and deserve attentions, and better not to be violated (with certain

exceptions in some special situations) to invoke jokes or ridicules from

experts or connoisseurs of Chinese calligrapainting. The rules and norms are adapted from

Chinese books and various Internet sources. You may use Google Advanced

Search to find out how many Chinese Websites have articles containing

these norms or rules regarding using Chinese seals on Chinese

calligrapainting and how many English Websites talk about these norms

and/or rules. A good way to verify this is to search "一方形,一圓形,不可匹配" or other short Chinese phrases

in the following articles in Google Advanced Search. It is certainly

true that a native Chinese, whether practicing Chinese calligraphy and

painting or not, may not have heard those rules and norms during his

lifetime... This is analogous to that people in certain parts of the

world learning different languages may not be able to imagine the

differences of grammar or syntax between English, Russian, Chinese, and

other languages. What we have not heard or imagined does not mean

certain things do not exist.

A teacher talks about dating, signing and using seals according to traditional norms

A teacher talks about signing and using seals at the right locations of a work

Some paragraphs are translated into

English "literally" by me. To maintain objectivity, I have

tried to remain faithful to the original Chinese texts except correcting

some of the typos or changing punctuations to be more readable. If you are doing so-called Modern

Chinese Calligraphy or Modern Chinese Painting in innovative approaches

or Xieyi styles, you may or may not need to observe some or most of the

norms listed below. But if you are doing Chinese calligrapainting in

traditional approach or with classical spirit, you need to pay attention

to those rules; otherwise, experts and connoisseurs ( 鑒賞家 ) will ridicule your work if you unknowingly violate some of the

“general” (but not absolute) norms. Sometimes they just laugh in

their heart or smile without giving you any compliment - they remain

honest and polite, but not diligent – they don’t tell you

exactly which norms have not been observed, especially when it is not

possible to explain many topics in a short conversation.

|

|

印章的種類 Kinds of Seals 名章 (Name Seals) 名章泛指作者姓名、字號等代表作者身份的印章,用于作者落款之後。一幅作品有兩方以上名章時要有陰陽變化,且大小最好相近,間隔至少一個章的空位。名章有時也可作手章使用,因其意義比較嚴肅,固以方形為主。 關於姓名、字號的區別 A

list of Style Names and Studio Names of Chinese Painters 閑章 (Mood Seals, literally Leisure Seals) 閑章是為了豐富畫面、完善構圖而用的章。內容多為與作者的喜好、作品的內容有關的詞句或形象(如座右銘、作畫時間、作畫時的心情、作品的寓意等)。 Joshua’s

comments: The contents of the Mood Seals need match the contents of

calligrapainting work. You cannot paint a love scene with a man and a

woman dating in a beautiful landscape with relaxed and romantic mood

and then stamp Mood Seals that say something politically like “Fight

for your country with loyalty to the end of war” or “Destroy your

corrupt government with justice” or "Practice martial arts with

endurance and strong will." Many people today (not only beginners

or non-Chinese) eagerly want to show off their seals by stamping as

many as possible on their work without considering the factors listed

here. Redundancy, mismatches, impolite implications, and wrong

locations are the most commonly seen errors of using seals on Chinese

calligrapainting. Of all kinds of seals, Mood Seals are usually one of

the most abused seals on Chinese calligraphy and painting.

根據用印的位置又可將閑章分為三類

Mood Seals can be further

categorized into the following types according to the locations where

they are stamped on a work: 1.

引首章

(Leading Seals):用于作品的右上方,與落款相呼應,又與畫面融為一體,因此多以自然形為主。 If

you gift your calligrapainting to others and write the recipient’s

name on the top right corner, you may not stamp your Leading Seal

above the recipient’s name because this imply that you are looking

down on him/her according to Chinese culture’s perspective –

Chinese will most likely consider it as an insult! The proper ways

are: you may either write the recipient’s name on the left side and

stamp your Leading Seal on the right, or write the recipient’s name

on the top right corner and stamp your Leading Seal below his/her name

in an appropriate spot. We also need to consider the philosophical

implications and spacing of Heaven, Earth, and Man in Chinese

calligrapainting when using seals. 2.

壓角章

(Corner Seals):用于作品下方的一個角上,起降低畫面重心、穩定畫面的作用,以方形或長方形為主。 3.

腰章

(Connecting Seals, literally Waist Seals):作品中間部位所用章。比較長的作品,視覺上的首尾不能相及,用一腰章能起到連接首尾的作用。多用長條或隨形章。 收藏章 (Collector's Seals):用于書籍等私人收藏。方形、圓形都可,偶爾也有隨形。印面要大小適中,以免造成對藏品畫面的破壞。 手章 (Hand Seals):指簽署文件、契約等用的私人印信。章面要小,字體要規範。

|

The signatures and seal stamps on

Chinese painting and calligraphy works follow strict or general norms and

traditions. If they are violated, a work will be mocked or demeaned because it

is considered ignorant and impolite in the eyes of cultured Chinese. It is sad

that the majority of calligraphers and painters today seem to neglect those

norms.

|

一般書畫家,差不多都有一些自用的印章,有姓名印、齋館印、別號印、里氏印、詩詞印、吉語印或啟事印。這些印如果用的不得當,不但不能為書畫增色,且可招致笑談。所以用印不可不慎。 古人用印都有法度,凡晚輩或屬下致書於尊長的,都用姓名印。平輩相交用字印。尊長與晚輩方可用道號印。用於詩文書畫,如僅用一印,則用姓名印;如用兩印,則姓名印在上、字印在下;用三四印,則姓名印第一、字印第二、道號印第三、齋館印第四。因為先有姓名,再有字、號、齋館,所以不能先後倒置。 用印時,如用兩方印,古法是白文與白文合用、朱文與朱文合用; 近世則朱白文合用,普通為白文印在上、朱文印在下,有名有字,即為對章。在畫幅中用印時,尤需注意印之距離與高低,如寫七言的對聯,下聯落款宜在第三字與第四字之間,而用印則應視款字的大小而定,若印為一寸大小,用兩方印時,兩方印相距應一寸左右,過遠過近均不甚雅。如寫一幀單條,則落款必須在主文左下方,但不可太靠下方,不然,與主文平腳,則印無法鈐蓋,即使留有一印之空白,將印鈐蓋其上,亦必不適宜。書畫落款固然重要,而鈐印則視款之高低而定,如落款不小心,過於低落,可以把印鈐在姓名左邊,使豔紅的顏色,襯於黧黑之中,便可反俗為雅。 印之大小,總以較款字稍小為合度,若大於款書,則有喧賓奪主之勢;又有聯珠印,刻二小印,中有距離而印身相連,若倒凹字形,可用於扇箑及小形書畫。此事雖無定法,但多看古人書畫,即可了然於心。 書畫上用的閑章多為詩文印、齋館印,方的、長的、自然形的都有。長方的或橢圓的以及自然形的,可以作為「引首章」用。所謂引首,用於書幅開始或畫幅題字的起首第一字或第一二字之間,視幅度的長短、印章的大小稍有高低,但總在開首部份。詩詞文句印、齋館印、吉語印乃至肖形印,不論方的、圓的、自然形的,如果形狀較大,均可以用於書件的右下角、畫件的左右下角,謂之「押角章」。押角必須書畫件的角落有空白之餘地,襯上一方紅色印章,使之更為生色,但鈐蓋的位置不可太低,低則有侷促之感,應離書畫件之邊角有適當距離,視印之大小與書畫件大小而定。個別欣賞印章是一種藝術品;配合書畫的印章又是另一種深刻的情味。顏色的對比、空間的安排,醞釀著雋永可感的美,「篆刻藝術」就這樣把美感的層次,提昇到更高的境界。 (摘自王北岳篆刻藝術 Adapted from Wang Bei-Yue's Art of

Seal Carving) 用印題款的忌諱 Taboos

of Signatures & Using Seals on Chinese Calligrapainting 書畫上落款蓋印,印比字大太多不可以。大幅蓋大印,小幅蓋小印,理所當然。 國畫直幅落款字下蓋印,直下底角不可再蓋壓角閑章。如右上落款,左下角可蓋閑章。左上落款,右下角可蓋閑章。如上款字印接近下角,閑章就不需蓋。 國畫直幅落款,左右兩頭角邊,不可蓋閑章。右上落款,左下角可蓋方形閑章。左下落款,右下角可蓋方形閑章。此處如不需要蓋閑章而勉強蓋上,反而弄巧成拙。 長方形,圓形,長圓形閑章,不可蓋在下角方形壓角閑章處之地位。 方形閑章不可蓋在書畫上端空白處,喧賓奪主。 國畫直幅落款,字行末行末字與他行字長短不可整齊,蓋印亦如此。 蓋二印,一方形,一圓形,不可匹配。同形印可匹配。 蓋二印,一大一小,不可匹配。同樣大小可匹配。 蓋二印,一長方形,一橢圓形,不可匹配。同形印可匹配。 蓋二印,上陽文,下陰文,不可匹配。上陰下陽可匹配。 蓋二印,上陽文,下陽文,不可匹配。上陰下陽可匹配。 蓋二印,上陰文,下陰文,不可匹配。上陰下陽可匹配。 落款蓋印之下,不可再題字。印章上下有字掣肘,就失去自然現象。 已經落款蓋印字畫,款後不可再落上款贈人,就失敬了。 花頭,鳥尾,樹枝,山頂上,不可落款蓋印。這是畫家最起碼的常識,不可不懂。 匠刻印章不可用於書畫上,需用藝術篆刻家所刻石章最佳。 Seals carved with machines cannot be used on Chinese

calligrapainting. We need to use seal stones carved by artists. 普通印泥不適用於書畫上,要用八寶印泥。 Cheap seal paste associated with machine carved seals or commonly

used in business offices cannot be used on Chinese calligrapainting.

We need to use authentic seal paste - in Chinese we call it 篆刻印泥 . 蓋二印,距離不可太遠太近,相隔一個印距離正好。 蓋二印,印文,章法,刀法各異,不可匹配。要用相同刀法所刻印章。 畫上不可題打油詩,一來識者奚落,二來作品就貶為低俗。 上款上端不可蓋閑章,壓在人名頭上,人家很忌諱。一來失禮,二來破壞了畫面。 If you gift your calligrapainting to others and write the recipient’s name on the top right corner, you may not stamp your Leading Seal above the recipient’s name because this imply that you are looking down on him/her according to Chinese culture’s perspective – Chinese will most likely consider it as an insult! The

proper ways are: you may either write the recipient’s name on the

left side and stamp your Leading Seal on the right, or write the

recipient’s name on the top right corner and stamp your Leading Seal

below his/her name in an appropriate spot. 蓋壓角閑章不可太小。宣紙四開,用方形石印大約三公分比較適合。 蓋壓角閑章,不可蓋二方以上,一方正好。印與邊距離 about 1.5 or 2 cm 為適合。 落款字下不蓋印,而偏要蓋在款字左右,脫離字行,而成畫外物,特殊情形例外。 書畫上,不可蓋上劈頭大印,破壞美麗的畫面。 (Except

for ancient emperors, don't put an extra large seal in the top middle

portion of the calligrapainting. If you do that, people think you are

arrogant or self-centered, or just ignorant! If you want to mimic this

as some ancient calligrapainters did, try to improve your

calligrapainting skills and knowledge first before others give

negative comments.)

Generally, 小畫不可題大字,大畫不可題小字。小空不可題字多,大空不可題字少。 書畫上姓名印,不可連蓋三印以上,應蓋二印,或一印妥當。 書畫上下左右,不可任意蓋印。蓋多不當,不如少蓋。印章印泥不佳,倒不如不蓋好。 (Many

laymen like to put as many seals as possible on their work to show off

without considering or knowing those norms and general rules...)

書法四聯首幅,右上可蓋印首小長形章,其餘不可蓋。 蓋二印,不可東倒西歪。如何蓋法,用力輕重,印章印泥保養,要潛心研究,是不可忽視的問題。 Many

people today apply excessive pressures and forces when stamping seals

on calligrapainting in inappropriate ways which are commonly seen in

public. This lady explains

in

logical ways why those ways are not so correct or simply wrong when we

also consider the correct ways to protect the fibers of the seal paste

and to "maintain the oil quality and level."

|

The following sources provide excellent articles and examples for signatures and seals.

http://home.pchome.com.tw/art/snowkaku/000.doc (File currently N/A)

http://www.books.com.tw/exep/prod/china/chinafile.php?item=CN10661666 歷代書家詩詞章法舉要(上下冊)

"Erasure

is an unacceptable mistake: If we do this, our work won’t be accepted or sold.

Ancient calligraphers did not care so much about erasing or covering a wrong character with a right one. They did this naturally and the work looked even more enlivened. While in our modern time, if any Chinese calligraphy stroke is covered with another one, the work will probably never win a contest or be sold. "Erasure" (or covering one stroke or character with another stroke or character) as shown in the following example is totally different from "amending or retouches" (repeating a stroke.) While a retouches or repeating a Chinese calligraphy stroke is considered a camouflage and dishonest, "erasure" is considered a change of content. ("Erasure" here does not mean to scratch off the strokes or characters to be changed.) "Erasure" does not violate the rule that the brush writing should come directly from one's mind and real skill. While an amended brush stroke can be easily told by experts because it shows evidences of inconsistent ink densities, "erasure" honestly tells the viewers that the "contents" of the calligraphy have been changed and they are not related to one's brush stroke skills. (In Chinese calligraphy contests, judges sometimes use magnifiers to look for inconsistent ink densities as evidences of retouches and get rid of those candidates.)

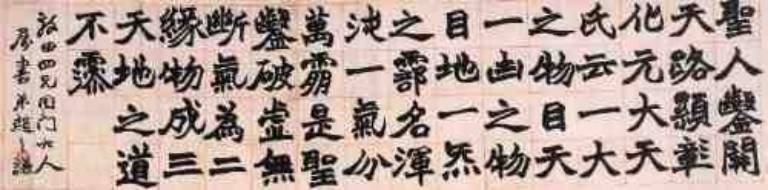

Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection (Lang Ting Prologue) is the most famous Chinese calligraphy work by Wang Xizhi. It contains more erasures than most other works! The erasures here are to change the content of the article, not to amend the calligraphy strokes. Amending strokes is not permissible for an honest calligrapher and anyone who practices Chinese calligraphy.

Another famous work full of "erasures" was written by Yen Jen-Chin in lamentation of his nephew being killed in a military riot. During writing this Eulogy for a Nephew, he was so sad about his nephew's death and had no intent to make it an artistic calligraphy work, and he even struck out thirty-four characters. However, this work is generally considered the "second best" cursive style calligraphy throughout the history of China! (Second only to Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection .) Viewers may feel his emotional intensity through his masculine, determined, agitated yet skillful brush strokes. While some beginners may think this work is full of mess and erasures and question why it is being collected in the National Palace of Museum in Taipei, the Chinese people look for the spirit and intrinsic substance over the extrinsic forms and neatness in a masterful work like this.